Summer 2009: Of Note

outbreak: Hubert professor of Global Health Carlos del Rio was one of the first experts called when the H1N1 virus broke out in his home country of Mexico.

Ann Borden

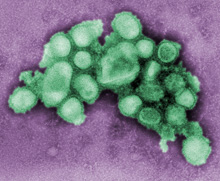

The H1N1 virus as seen by an electron microscope.

C. S. Goldsmith and A. Balish/CDC

Flu Fighters

Emory scientists are on the front lines in the H1N1 flu pandemic

More Coverage

For more Emory H1N1 coverage, go to the Woodruff Health Sciences Center's H1N1 Influenza page.

By Mary J. Loftus

Late on the evening of April 22, Hubert Professor of Global Health Carlos del Rio 86MR received a call at home from the secretary of the treasury in Mexico, who is also a good friend.

“Please tell me all I need to know about swine flu,” he said. “I am going to an emergency meeting with the president to discuss a possible outbreak.”

The next day, del Rio was on a plane to Mexico—his home country, and where he attended medical school—and was soon working with colleagues in Mexico City to try to understand the outbreak, develop sound policies, and serve as a liaison with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“On one side the city was empty, like a ghost town. On the other the population was frightened and anxious, asking for information,” he says. “In the hospitals, there was a sense of crisis. Emergency rooms were full of patients with influenza-like illness, and wards and ICUs were full of patients with viral pneumonia.”

On June 11, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared H1N1 the first pandemic in forty-one years, with the disease present in more than seventy countries. By midsummer, there were more than thirty-seven thousand cases in the United States, including 138 in Georgia; the first student case at Emory was announced on June 19.

Del Rio is just one of dozens of scientists at Emory working to stem the H1N1 (swine flu) outbreak, advising public health and government officials here and abroad, developing diagnostic tests and therapies for H1N1, and working on producing quick, effective vaccines.

A group of Emory’s infectious disease experts, vaccine scientists, immunologists, and microbiologists helps make up the Emory-University of Georgia Influenza Pathogenesis and Immunology Research Center, one of six national NIH Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance. According to Vice President for Research David Stephens, this network of centers is directed to be on the front lines in a pandemic.

“The pairing of Emory’s expertise with strengths at UGA in animal pathology creates a uniquely effective combination for studying crossover viruses such as swine flu,” says Richard Compans, director of the Emory-UGA center.

This unique flu strain—which includes genetic material from human, avian, and swine flus—can spread from person to person. Scientists in Emory’s flu research center are looking at how the H1N1 virus enters cells, how it is transmitted, and whether prior exposure to other influenza viruses may help immune responses to the new virus.

Upon his return to Atlanta, del Rio joined a think tank of outside experts who act as advisers to the CDC’s Influenza Team. Foege Professor of Global Health Keith Klugman is also a member of the group. “My role is to consider bacterial infections that may cause severe pneumonias associated with influenza epidemics,” he says. Associate Professor of Pathology Jeannette Guarner worked with colleagues in Mexico to obtain autopsy/biopsy materials, which she took to the CDC for testing.

Emory Vaccine Center Director Rafi Ahmed and colleagues, working long hours in the lab, have discovered a way to speed up the production of large quantities of infection-fighting antibodies, called human monoclonal antibodies, that can boost the immune system. These antibodies, which could target H1N1, are created by using just a few tablespoons of blood drawn from volunteers inoculated with the influenza vaccine and can be used as a diagnostic or a therapeutic tool.

“The National Institutes of Health have asked us to redirect our efforts to H1N1,” says Jens Wrammert, a researcher at the vaccine center. “Immediately, we are seeking a potential treatment.”

Emory and CDC researchers also are using virus-like particles to develop a quicker, more efficient alternative to the current method of making flu vaccine by growing it in chicken eggs.

Microbiologist Ioanna Skountzou and her team at the influenza center are working on skin patches that contain microneedles as an improved vaccination method. The center has been growing the H1N1 virus from a sample.

“It’s not an easy thing to grow a virus—especially a new virus that hasn’t been processed before,” she says.

The pandemic, Skountzou adds, may still pose a threat. “In cold weather, people are more prone to diseases. We will have to wait and see what happens.”