Cycle of Giving

Bequests by Woodruff and family inspire Amy Toy Rudolph and Toy Scholars

Amy Toy Rudolph 88C 91L was the only person left in her immediate family after her mother died in 2005. Her dad had died in 2002. She was an only child, and theirs had been a tight triangle. They had cared for her, and as they aged, she had taken care of them.

In her mother’s will, she discovered their wishes to extend that care to others. A bequest to Emory signaled a new role for her family: Two generations of Toys had benefited from college scholarships, and now they were the givers. “Emory had given me this wonderful education that has continued to enrich my life even after graduation, and they wanted to repay it in some way,” Rudolph says.

Today the Toy Family Scholarships in the School of Law and Emory College represent the power of higher education to change families and inspire investing in exceptional students. Rudolph’s father was financially able to attend college during the Depression with the help of a teacher who saw his potential and lined up a scholarship; her own education was possible because of the generosity of the legendary leader of The Coca-Cola Company, Robert W. Woodruff 1912C. Today the first two Toy Scholars, Anna Altizer 08C 13Land David Mayer 02C 13L, augment the family’s legacy as they start their law careers.

“My parents didn’t say what they wanted done with their bequest to Emory, but I thought scholarships would be fitting,” Rudolph says. “I knew Emory was prioritizing relieving the financial burden for students, especially ones who wouldn’t otherwise be able to attend.” In Rudolph’s family, that was a familiar story.

North Carolina: A Teacher’s Vision

James H. “Jim” Toy graduated valedictorian of Waynesville High School in 1937, close to Cold Mountain, in the grip of the Depression. His father had been disabled in World War I, and Toy planned to work to support his family.

Rudolph recalls her dad’s retelling how a teacher asked him where he was going to college. “We can’t afford college,” he replied. “I’m pretty good with numbers. I’ll get a bookkeeping job somewhere.”

The teacher refused to accept his answer. She contacted friends with connections in higher education, who lined up a scholarship and work-study opportunities at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). “Off he went, and it changed his life,” Rudolph says. “He graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1941. He lettered in cross-country and track. A more loyal Tar Heel could not be found.”

His college degree paid off. He worked as an auditor for Arthur Andersen in Atlanta, where he met and married Pauline “Polly” Jordan, who had been senior class president of what is now Valdosta State University. They moved to upstate South Carolina, where as a certified public accountant he handled financial management and accounting at the Milliken Textile Research Corporation.

South Carolina: Raised to learn

Toy was forty-five and his wife almost thirty-nine when their only child was born. Rudolph remembers her parents’ limitless appetite for learning. Not only did they own, for example, the eleven-volume series The Story of Civilization by Will and Ariel Durant, but Jim Toy read its ten thousand pages. “He was a voracious reader and so was my mom,” she recalls. “From them I never got the impression that there was something I wouldn’t be able to do. There was nothing off limits, and it was important to work hard and do the best you could.”

Like her dad, Rudolph graduated valedictorian of Spartanburg High School in 1984, her academic stature accented by her six-foot height—higher when she was in the mood for heels. She won state accolades in piano and oboe, soloed with the Spartanburg Symphony, and was a National Merit scholar.

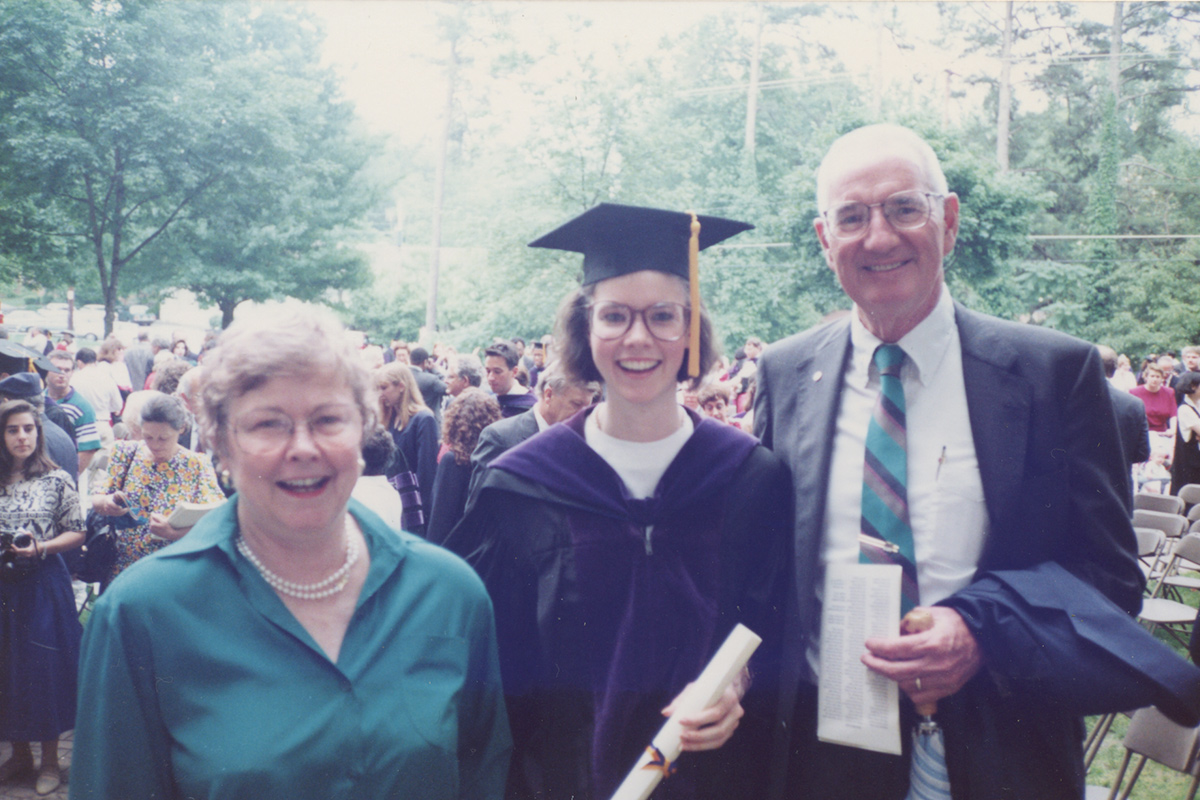

Family Values: Amy Toy Rudolph at her graduation from Emory's School of Law with her parents, Polly and Jim Toy, who she says had a limitless appetite for learning.

Jonathan Draluck 91L

With qualifications like that, she could have gone to nearly any university in the country. But she wanted to stay in the South for college, and Emory University—170 miles south of her hometown—offered a new scholarship that would pay her to learn.

In 1980, Emory had established the Robert W. Woodruff Scholars and Fellows Program to recruit and reward students with exceptional character, scholastic abilities, and leadership qualities. It was funded through “the Gift” in 1979, a transfer of assets that pushed the Woodruff family donations to Emory to more than $200 million. At the time, it was called the single largest charitable gift in American history, and a portion of it funded the scholars and fellows program. “The Woodruff” paid for all tuition and fees, and included a stipend for books and living expenses. Today the value of the Woodruff Law Fellowship, for example, is $150,000.

Emory: Raising the bar

“The Woodruff Program has more than anything else changed the mix of students at Emory,” says Associate Professor of Economics Christopher Curran, who joined the faculty in 1970 and became Rudolph’s honors adviser. “Woodruff Scholars change the atmosphere in a classroom. They are willing to talk, pay attention, and show leadership. Students in Amy’s class got to see what it meant to work hard and come prepared. She provided a different example of intellectual curiosity, of learning just to learn. Woodruff Scholars pull other students along with them. The Woodruff Scholars bring a different set of attitudes to the classroom that makes it more fun to teach.”

Momentum was high among the scholars and fellows. They dined at The Coca-Cola Company headquarters and immersed themselves in Woodruff lore. “I remember his watchwords: ‘There is no limit to what you can do if you don’t mind who gets the credit,’ which seemed to be the spirit of Emory—a place with subtle charms, not self-aggrandizing, but that encourages you to service,” Rudolph says. “There was a sense of excitement about the Woodruff Gift and what it meant to the whole university, and we were part of a multifaceted effort to take maximum advantage of what the gift could mean. I wanted to live up to it.”

Majoring in French literature and economics, Rudolph pushed herself to new challenges in and out of class. With no journalism background or political leaning, she became editor of the nonpartisan political monthly the Voice. She wasn’t a singer, but she joined the Emory Chorale and performed under the baton of famed conductor Robert Shaw.

“Amy was poised, self-confident, friendly, and engaging. She always came across as brilliant,” says Theresa L. Burriss 88C, her sorority sister from Kappa Alpha Theta. “She appeared to know who she was when she arrived, and it seems to me Amy only solidified her identity over our four undergraduate years at Emory.”

“No matter what she did, she threw herself into it,” Curran says, offering a course as one example: “The joint mathematics-economics class is one of the harder courses at Emory, and it wasn’t precisely her strength, but she did well because she has a lot of energy and willingness to work. If she hadn’t received the Woodruff Fellowship for law school, Emory wouldn’t have retained her.”

Rudolph is modest about the “double Woodruff,” joking that “Emory was gullible twice.” She had picked economics because she liked learning about incentives, rewards, and costs; something about law made her brown eyes light up.

When she graduated from the School of Law, her father reminded her of her great fortune: “People don’t have to give you anything. That’s why it’s a gift. And you are privileged to have received that gift,” he told her. “Make sure you give.”

Atlanta: Answering the call

“Boy, is she having a great career,” notes Thomas C. Arthur, LQC Lamar Professor of Law, reading over Rudolph’s long resume of corporate litigation success and legal service. He had taught her antitrust and observed her as a law student already involved in alumni events. She also edited the Emory Law Journal, one of several volunteer hats she wore. “I never heard her use the words ‘giving back,’ ” he said. “She just naturally did these things. She was not a salesman or super extroverted. She was always there to put her shoulder to the wheel.”

Loyalty—like her dad’s loyalty to UNC—distinguishes Rudolph’s career achievements and service to Emory. She is a partner in the corporate litigation practice group of Sutherland Asbill and Brennan, based in Midtown Atlanta, five miles west of campus. She joined the firm after a clerkship under US District Judge William C. O’Kelley 51C 53L, who inspired her professionally and in his service to Emory.

“I’m old school in many ways,” she says. Despite a hectic travel schedule, when asked to volunteer at her alma mater, Rudolph says yes as much as possible. She helped restructure and lead the Emory Law Advisory Board, serves on the Emory College Alumni Board, and has helped select many Woodruff recipients and Dean’s Achievement Scholars.

“She’s made three big contributions by helping make our leadership stronger, directly helping individual students as a mentor, and financially as a donor,” said Gregory L. Riggs 79L, the School of Law’s associate dean for external relations. “Through her time, judgment, experience, and creativity, she is giving of herself now, and her family scholarships will be touching students for generations to come.”

She also has inspired fellow alumni to get more involved. “It was very significant to me that Amy had faith in me and my ability to serve on the Emory College Alumni Board,” says Burriss, who now directs the Appalachian Regional and Rural Studies Center in Radford, Virginia. “The board is the core of our institution because the college is where Emory started as an institution. Amy’s connections and legal experience benefit the board and the college. For me, it’s so inspiring to be around other alums who have the Emory ethic, namely a commitment to serving society and a desire to make a difference, on whatever scale.”

On the quad today: Going forward For Anna Altizer 08C 13L, the Toy family gift represented another alumnus reaching out to make a difference. Paul C. McLarty 65Cand his wife Ruth McLarty had befriended her as a freshman; Altizer had worked in McLarty’s law firm, which helped her land a job in commercial real estate at McKenna Long and Aldridge, and he took part in her hooding ceremony at Commencement. “Alumni taught me the joy of giving back to the university to support students and provide opportunities for them to thrive,” Altizer says.

For David Mayer 02C 13L, the Toy Scholarship reminded him of his own Woodruff connection. While at the School of Law, Mayer landed an externship at The Coca-Cola Company’s trademark office. “The trademark is the embodiment of the goodwill of the company, and Coca-Cola is the No. 1 trademark in the world,” Mayer says. “Woodruff made Coca-Cola a household name—he made the company what it is today and became a very good friend to Emory.”

Both Altizer and Mayer hope to do for others what the Toy family has done for them: fund scholarships for future students. They see themselves as part of the cycle of receiving and giving that shapes families, higher education, and Emory. “It was very interesting and inspiring to know that there were people who had set up special funds for people who had come back to Emory,” Mayer says. “That could be me someday helping someone else, helping benefit another student down the line.”