Second Chances

What if you could relive your days at Emory—again, and again, and again?

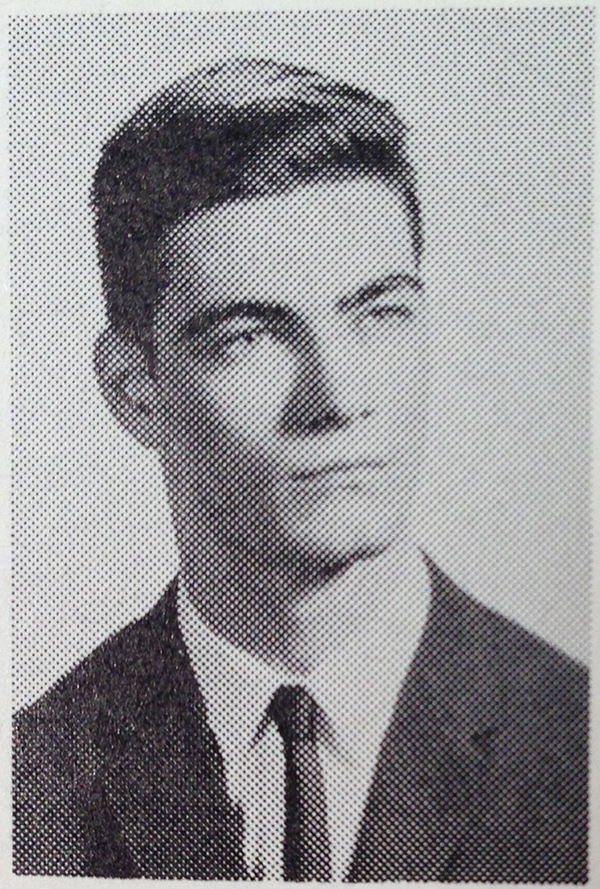

Ken Grimwood himself, as seen in the 1962 Campus yearbook

The college years are a time of momentous change.

You probably heard that several times over at your Emory Commencement. You also very likely heard something similar at your freshman Convocation, from your adviser, from your parents. You may have since trotted out that same chestnut for your own kids. It is, of course, no less categorically true for being appallingly trite. For better or worse, college counts. It’s a time when dice are cast, decisions made, some of which really can affect the course of an entire life.

It is therefore natural that glancing back at those years (say, through an occasional dip into the alumni magazine) stirs both nostalgia and the occasional twinge of regret or, at least, of speculative revisionism. Now and then, even if only for a moment, you gotta wonder how things might have turned out if you had zagged, junior year, instead of zigged. What if you’d passed on (or jumped at) that semester abroad? Where might you be today if you’d stayed with that girl, that guy, that philosophy major, that woodwind instrument you slavishly practiced all through high school and then ditched because rehearsals clashed with your Greek chapter meetings?

And what would you do if you had a second chance—if, knowing what you know now, armed with all those hard-learned life lessons, you could go back, back to Emory, back to when your cholesterol was low and your hopes were high, and start all over again?

This tantalizing prospect is the central conceit of Replay, a cultishly classic 1987 novel by Ken Grimwood 65C. The protagonist, Jeff, a mid-lifer with a sagging, childless marriage and a lackluster career in local broadcast news, drops dead at his desk from a heart attack in the late 1980s—only to wake up, eighteen again and in his old freshman dorm room in Longstreet Hall at Emory in 1963. Inexplicably rejuvenated, Jeff is suddenly back in college, before Vietnam, Woodstock, and Watergate, before the Beatles, VHS, and MTV—and of course, he is late for an exam.

Replay initially takes this solid sci-fi setup down a fairly predictable path. After the inevitable culture shock and some less-than-successful stabs at changing the course of history writ large, Jeff seizes this seemingly golden opportunity, using his memories of the future to his financial advantage. By the time he reaches his forties for the second time, he has gone from a wunderkind gambler picking winners with uncanny accuracy (in the few horse races and World Series he previously paid attention to, anyway) to a Wall Street tycoon, complete with a chilly blueblood trophy wife, riches beyond his wildest dreams, and a daughter he adores.

But second chances aren’t all they are cracked up to be in Grimwood’s world. On the anniversary of his first demise, Jeff succumbs a second time to the same fatal heart attack and lands right back at his alma mater, arriving in his personal past just a few weeks later than the last time, his fortune, his family, instantly erased. Two lives lived. Two lives lost, and a third now stretching out before him. The realization nearly breaks him:

“He raced through the quadrangle, past the chemistry and psych buildings, his strong young heart pounding in his chest as if it had not betrayed him minutes ago and twenty-five years in the future. His legs carried him past the biology building, across the corner of Pierce and Arkwright drives. He finally stumbled and fell to his knees in the middle of the soccer field, looking up at the stars through blurry eyes.

‘F--k you!’ he screamed at the impassive sky with all the force and despair he’d been unable to express from that terminal hospital bed. ‘F--k you! Why . . . are . . . you . . . DOING THIS TO ME?’ ”

The perverse time loop that traps its protagonist is the ingenious engine that sets Grimwood’s story apart from other time travel tales. Far from enjoying an infinitude of cosmic do-overs, Jeff and his fellow “replayers” are sentenced to relive their lives but cannot dodge their deaths. They do not so much live forever as eternally die, their apparent immortality a perpetual existential crisis.

Grimwood was himself a student at Emory College in the early 1960s; he left the university in 1963 and later graduated from Bard College in New York. His own marriage hadn’t lasted, he had no children, and, like his protagonist, the author worked in new radio until the success of Replay freed him to focus on fiction. In some ways, then, the novel reads like a Twilight Zone take on the memoir, a series of deftly sketched might-have-been autobiographies. Over the course of his reiterative existences, Jeff explores a whole range of possible identities—wizard of finance, hedonistic pre-HIV swinger, middle-class family man, recluse, do-gooder, guru—none of which ultimately works out all that much better for him than his first go-round.

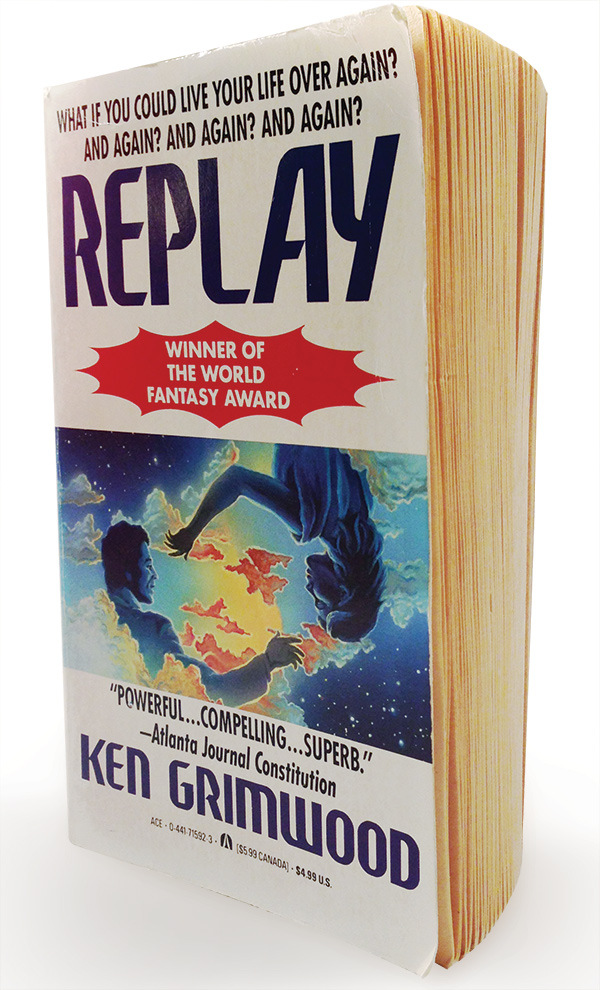

Dean Robin Forman's original copy of Replay

Though it is usually described as either science fiction or fantasy, it doesn’t fit smoothly into either genre as they are popularly understood. Fans of “hard” science fiction will find Replay terribly thin—no plausible explanation is ever given for Jeff’s temporal predicament. Nor is the story a fantasy in any swords-and-sorcerous sense. There are no magic spells or demonic forces at work, and if Jeff is cursed, it is never revealed by whom, or why. Still, Replay struck a chord. The novel sold well and was awarded the 1988 World Fantasy Award for Best Novel, a prestigious prize in the speculative fiction field, and short-listed for that year’s Arthur C. Clarke Award.

It also has staying power. Grimwood’s best-known book, it has never been out of print, and Replay routinely crops up on lists of the greatest works of speculative fiction compiled by critics and connoisseurs.

“For a book to take such bizarre circumstances, and somehow make it real enough that you can imagine yourself in it, is quite a remarkable accomplishment,” says Emory College Dean Robin Forman, a fan who first encountered the novel twenty years ago and recently discovered it in his basement, prompting him (and subsequently Emory Magazine) to explore Grimwood’s Emory connection. “I rarely reread books . . . but Replay is one of those books I’ve kept.”

By and large, Replay eschews the sensational. World saving and paradox wrangling, a la Terminator, Looper, et al., are kept to a minimum. The one lifetime Jeff dedicates to Nostradamusing in the name of national security is an utter failure, the replayers’ best efforts leading only to disillusionment and dystopia. History, Grimwood seems to suggest, is out of any one person’s hands (a position some might justly call a cop-out). The late-twentieth-century’s wars, assassinations, and major-key misery erupt over and over again around the replayers, just as Jeff’s heart always fails on cue.

The book is rather far more interested in, and the protagonist far more affected by, the kind of nickel-and-dime drama we can’t really notice most of the time because we are so constantly immersed in it. Jeff’s peculiar plight, his growing world-weariness and sense of strangeness, throw into sharp relief the banal, bewilderingly complex and constantly evolving rituals of courtship, friendship, and marriage; the futility of materialism and emptiness of wealth; the quotidian tragedy of having a really, really great afternoon, all the time knowing it will vanish into the yawning well of the past.

As each life passes for Jeff, each shorter than the last, he becomes more keenly aware of the preciousness of everything he experiences— everything he, and all of us, are doomed to lose. Unable to save humanity, unable to save even his life, Jeff learns to savor it instead. The intimate and intensely human dimensions of Replay give the story poignancy and impact unmatched by many works drawn on a far grander scale.

“There’s a tendency to look at your life as a big single simple narrative with big themes, and I think that’s not really what life is,” Forman muses. “Life is a series of smaller moments that add up to something bigger. Those simple pleasures are the big thing in life.”

Replay reminds us not only how much our world changed during the course of the latter half of the twentieth century, but also how much the way we live in it has changed. History, often rendered on a grand scale and preoccupied with potentates and entire peoples, becomes playfully, vivaciously personal as seen and reseen through Jeff’s eyes, a history written through mores and movies, shifting skylines, hemlines, and habits.

Those with memories of their own of Emory and of Atlanta will find some special treats in Replay—glimpses of an Emory before coed dorms, before the bonanza $105 million Woodruff gift of 1979, an institution, in 1963, just over the threshold of integration in a city still decidedly segregated. It’s equally eye-opening to consider what places and practices endure from those days.

This is not to say that Replay is without its flaws, and Grimwood, as an author, has his limits. The story contains moments of cloying preciousness and pretension, and some of the angles played by Jeff and his eventual soulmate, a female replayer with a thing for the movies, smack of dream-date fantasies and adolescent wish-fulfillment (but then maybe that’s the whole point: if you knew decades in advance what the next big thing in fashion, film, and music would be, how mature would your decisions be?). But the story is also frequently compelling, sometimes clever, and never, ever dull—one encounter, with a replayer who turns out to be exactly the kind of guy you don’t want making return trips to the land of the living, is about as creepy as anything you’ll find in the best pop-lit thrillers.

“If pressed, I wouldn’t call it great literature,” Forman admits. “[Grimwood] is not in that pantheon of literary immortals that we think of in those terms, but he found a story and a way to tell it in a way that resonated when it was first written, and it resonates today.”

Replay turned out to be the pinnacle of the author’s career. Like so many well-reviewed contemporary novels, Grimwood’s magnum opus was optioned, in 1989, for adaptation to the big screen. And, like so many, the movie version never materialized. Coming off a solid decade of high-concept blockbusters, Hollywood was plenty keen on science fiction and fantasy properties, but perhaps a bit bearish on films made from novels—the biggest hits of the period, such as Star Wars, E.T., and Back to the Future (which offered a different take on time travel) had gone the other way ’round: the box-office hits spawning best-selling novelizations.

Grimwood’s time-loop twist did eventually turn up in a different movie, though—the 1993 Harold Ramis comedy Groundhog Day, a film about a boorish TV weatherman stuck reliving February second. The film strikes many of the same chords as Replay and has won a cult following of its own. While it is frequently cited as an “inspiration,” Replay appears nowhere in the film’s credits.

Ken Grimwood died (in all likelihood just the once) in 2003. A film lover with decidedly cinematic sensibilities, he did not live to see any of his novels translated to film. Ironically, several more recent comedies have riffed on some of the themes he so effectively explored in 1987, including the 2002 television series Do-Over, and the films 13 Going on 30 (2004) and Seventeen Again (2009).

Interest in the novel has also seen a recent revival. Replay seems to be hard to forget, and to resonate particularly powerfully with men of a certain age. Ben Affleck was toying with the picture in 2011 (he moved on to a different, obliquely science-fictional period project, Argo, instead). Most recently, industry scuttlebutt has Robert Zemeckis, of Back to the Future fame, eyeing the adaptation. There would be some symmetry in this: Zemeckis has a track record with history-hopping dramas—he did give the world the film version of Forrest Gump—and his most recent film, Flight, was shot here in Atlanta.

It would be nice to see Emory host such a production, should it come to fruition, since the college clearly made so indelible an impression that Grimwood’s avatar is compelled to return here, life after life, just as the book’s many fans return to Replay time and again—drawn by that compelling desire to go back to the crossroads that set the course. For many of us, college may be that crossroads.

But despite its supernatural premise and occasional kookiness, Grimwood’s is at bottom a story of an ordinary human being learning how to live his life. It’s a process we all have to grapple with. Hopefully, most of us won’t need a couple hundred extra years and a whole lot of dying to get it right.