Georgia's Heavy Burden

The Peach State is No. 2 for childhood obesity—but a targeted program is helping families change for good

Kay Hinton

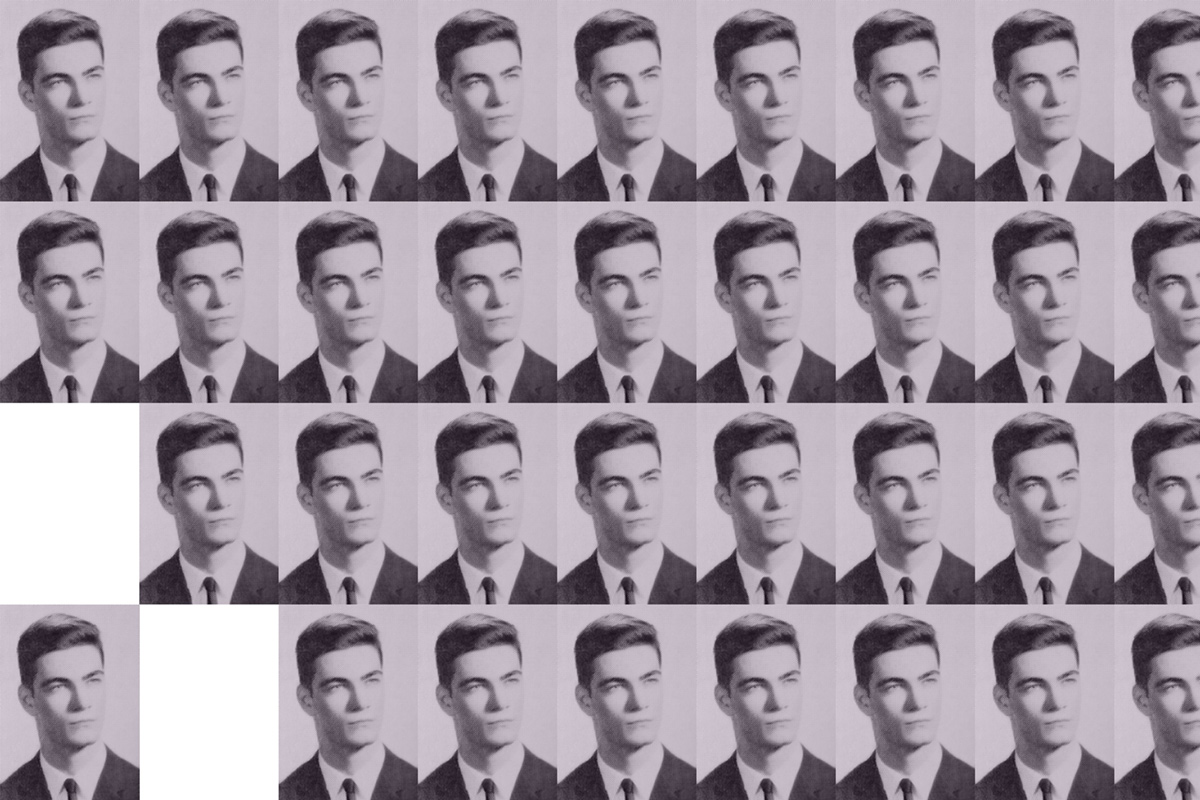

Collin Jackson was always what his mother calls a “big boy.” He weighed more than thirteen pounds when he was born and continued to top the weight chart as he grew up.

By the time he hit adolescence, it was clear that he was more than just a large kid; Collin was seriously overweight. His mother, Teresa Jackson, tried various diets, such as an egg-white-and-fruit regime when Collin was in the fifth grade. He lost weight, sure, but as soon as they relaxed the program the pounds came right back on.

During a recent visit to the Health4Life clinic at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, both Teresa and Collin were in tears as they described Collin’s first years of high school in their South Georgia hometown of Perry. A sweet-natured teenager, Collin was ruthlessly teased and picked on. Kids would come up to him, punch him, and take off, knowing that he would never be able to catch them.

“They would just assume things about me, that I only eat junk food,” Collin says. “They would make all these judgments, and they don’t even know me.”

When his nose was severely broken by a fellow student, Teresa had had enough. She pulled him out and began homeschooling Collin. But the bigger problem—his size—didn’t go away.

Last year after a visit to his doctor, Collin, who’s now seventeen, came to Teresa and announced that he was ready. He had researched weight-loss programs and had discovered information about Health4Life. His first appointment was October 2, 2012.

The whole family was impressed with the warm welcome and encouragement they received from the staff. “It’s like family, they are always smiling and making you feel good about what you’re doing,” Teresa says. “They told Collin they believed he could do anything he set his mind to.”

Led by Stephanie Walsh 89C 04MR, medical director of child wellness for Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, the Health4Life clinic takes a comprehensive, team approach to patient care: at each visit, families will likely see a physician, a nutritionist, a psychologist, and other experts as needed. It’s one of the few such integrated programs available to families, Walsh says.

When the team first met with Collin, they identified sugary drinks as a major source of calories for him—calculating that he was probably consuming close to fourteen cups of sugar a day in sweet tea and soda alone. He was instructed to cut back on those drinks and begin walking daily, adding a few minutes to his exercise each week. They also asked that Collin record every single visit to the kitchen, whether he got something to eat or drink or not.

That was basically it. “They let me set my own goals,” Collin says.

At a visit in late November, Collin was beaming with pride: he had lost eighteen pounds in six weeks, far surpassing expectations. He has cut out sugary drinks and is walking up to forty minutes a day. “Thanksgiving was a joy,” Teresa says. “We didn’t have to watch what he ate. There was still room left on his plate.”

Collin is one of nearly a million young people in Georgia who are overweight or obese—almost 40 percent of children in the Peach State, a staggering number topped only by Mississippi. Nationally, childhood obesity has increased by 300 percent in the past thirty years, Walsh says. And recent studies indicate that as many as 75 percent of parents who have overweight children don’t realize it. “The weight comes on slowly,” Walsh says. “Busy parents don’t always notice.”

In 2008, Walsh—along with Emory’s Miriam Vos, assistant professor of pediatrics in the School of Medicine, and Andrew Muir, Bernard Marcus Professor of Pediatrics—cofounded Health4Life specifically to address the childhood obesity epidemic in Georgia.

“We are looking for families who are struggling with weight issues,” Walsh says. “Most have struggled for a long time, and have tried and tried and tried to make a change. We have a lot of families who are very motivated and committed to their children.”

Walsh, Vos, Muir, and colleagues like Mark Wulkan 89M, professor of pediatric surgery and chief surgeon at Children’s, have been collaborating on cases for more than a decade and collectively watching the trend of childhood obesity grow to an alarming degree. Many of the children they now treat present health problems that were once almost exclusive to adults—hypertension, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol, and fatty liver disease.

“It’s interesting, as a pediatrician, to relearn how to take care of diseases that we didn’t take care of before,” Walsh says. “It’s also nerve wracking, since many of the relevant medications have only been tested on adults.”

Health4Life also offers bariatric surgery—usually removal of a large portion of the stomach—for extreme cases in which patients are at risk due to weight-related health problems. “The goal is not to make kids pretty for the prom,” says Wulkan, who performs about one such surgery a month. “It’s about their overall health. We have had kids lose over a hundred pounds, and these comorbidities all got better.”

For many families like the Jacksons, Health4Life, based at Children’s, is the last, desperate stop on a long and difficult road. The program, which has about 375 active patients at any given time, is targeted to whole families, since eating is a family affair; children with one obese parent have a 50 percent higher risk of being obese themselves, and with two obese parents, the risk rises to 80 percent.

Collin’s downfall, sweet drinks—which include fruit juice, sports drinks, virtually all liquids available to kids except water and plain, lowfat milk—are a major focus at Health4Life. Clinic experts also blame kids’ lack of physical activity, reduced play outside in favor of “screen time,” increased access to food at any time of day, and the proliferation of fast food and highly processed foods for their long-term growth in girth.

Thanks to attention in the media, health news sources, and promotional efforts like Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta’s Strong4Life—a broad, multifaceted campaign for public awareness—these problems are becoming part of the national consciousness.

“In the past, it’s been the high consumption of sugar or the lack of physical activity, but I am pleased to say that I think awareness of these problems is really changing fast,” says Vos, who is author of The No-Diet Obesity Solution for Kids. “There is still a long way to go, but schools are increasing PE again and public health campaigns like Michelle Obama’s ‘Let’s Move’ have made huge inroads into the awareness problem about sugar drinks and activity.

“The harder target is getting young people to eat vegetables and cooking good quality, healthy food,” Vos adds. “In some families, you have to go back several generations to find someone who knows how to cook.”

Launched in 2011, Strong4Life now encompasses Health4Life as its clinical arm, but its aim is to reach a broader audience through public awareness, policy change efforts, school programs, health care provider programs, and community partnerships. The “movement,” as its leaders call it, has reached some 250,000 Georgians in its quest to confront the childhood obesity crisis.

Strong4Life breaks lifestyle change down into simple steps, offering four basic rules for health: make half your plate vegetables and fruits, be active for an hour each day, drink more water and limit sugary drinks, and limit screen time to an hour a day.

Kids like Collin Jackson know that’s not as easy as it sounds. But because of the Health4Life clinic, Collin says he feels genuinely hopeful for the first time in his life.

“I just want to be average,” Collin says. “I don’t want people to look at me and laugh or make judgments when I have never even met them. I want to be a boy—not a fat boy. Just a boy.”