Research

October 26, 2011

Beckett letters illuminate reclusive writer's creative process

In 2009, Emory celebrated the first volume of "The Letters of Samuel Beckett, 1929-1940."

Samuel Beckett, the Irish avant-garde novelist, theater director and poet, once wrote that "every word is like an unnecessary stain on silence and nothingness."

His more than 15,000 letters, spanning six dynamic decades of the 20th century, tell a different story. They reveal a softer side of the self-effacing, reticent writer who refused to attend his own Nobel Prize ceremony and preferred to let the words on the page speak for themselves.

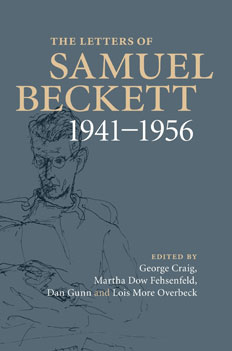

Published this month, "The Letters of Samuel Beckett, 1941-1956" (Cambridge University Press, 2011), is the much-anticipated second volume from a team of editors at Emory, the University of Sussex and The American University of Paris, assisted over a quarter century by more than 100 undergraduate and graduate students.

On Oct. 21, Emory's Laney Graduate School presented "Words Are All We Have: From 'Watt' to 'Godot,'" featuring readings by noted Irish actor Barry McGovern and Atlanta actors Carolyn Cook, Robert Shaw-Smith and Brenda Bynum, who is a former resident artist and lecturer with Theater Emory. Several Emory departments, along with the Consulate General of Ireland, the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs and the Consulate General of France in Atlanta co-sponsored the event in Glenn Memorial Auditorium.

Rounding out the festivities this month were film screenings of Beckett's work and a theater workshop offered by McGovern, known for his adaptations of Beckett's fiction for the stage.

"The Letters of Samuel Beckett, 1941-1956" is the second volume from a team of editors at Emory, the University of Sussex and The American University of Paris.

Special request

In 1985, Beckett authorized Martha Dow Fehsenfeld to edit a selected edition of his letters. Fehsenfeld had observed Beckett directing several of his plays including "Krapp's Last Tape" and "Endgame," in preparation for her 1988 book, "Beckett in the Theatre" with Dougald McMillan.

The Beckett Letters Project became affiliated with Emory's Laney Graduate School in 1990, and has since received four grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, along with support from the Florence Gould Foundation and other research grants.

The first volume of "The Letters of Samuel Beckett, 1929-1940," published in 2009, garnered international acclaim. It revealed a passionate and vulnerable young Beckett, immensely irritated by his own writing and the achingly slow pace of success.

The second volume primarily focuses on Beckett's post-World War II years, after he joined the French Resistance and was forced into hiding. It chronicles the beginning of Beckett's mature and most celebrated work written in French, including "Molloy," "Malone Meurt," L'Innomable" and "En Attendant Godot."

Beckett was nearly 50 years old when "Waiting for Godot" achieved public success, yet his relationship to the play — as with much of his other work — was one of "attachment" and "revulsion," the book editors write.

As Beckett wrote to his lover Pamela Mitchell in 1953 following the play's premiere, "I went to Godot last night for the first time in a long time. Well played, but how I dislike that play now. Full house every night, it's a disease."

Volumes three and four are expected to be published by 2015, along with a general-interest volume that will include elements of all four.

"Each of the volumes is like a kaleidoscope," says editor and project director Lois More Overbeck in the Laney Graduate School. "You give it a quarter turn and another picture emerges."

Epic effort

Building on a sparse collection of drafts donated by the writer himself, the researchers launched an ambitious effort to hunt through archives and private collections. Their meticulous legwork, grounded in patience and stamina, involved accounting for each and every book, painting and piece of music mentioned in Beckett's correspondence.

They contacted the French national meteorological service to verify historical weather patterns, consulted with Emory Eye Center doctors about Beckett's cataracts, and called every Desmond Smith in the Toronto telephone directory to locate the one who had written to Beckett in 1956 with questions about "Waiting for Godot." Smith, who was in the process of moving, ended up retrieving his letter from a box of old newspapers.

Beckett's letters were often undated and written in horrendous script due to his crippled arthritic finger and, at times, poor eyesight. While Beckett is widely regarded as one of the most influential writers of the 20th century, one manuscript dealer complained that his penmanship was the most difficult of all to decipher. Letters were often passed among the volume's editors — Fehsenfeld; Overbeck; George Craig, honorary research fellow at the University of Sussex; and American University in Paris professor Dan Gunn — littered with question marks.

"We're very pleased when we actually get one that's typed, though he would wear out the typewriter tape until there was nothing left," says project editorial assistant Melissa Holm.

Jan Steyn, an Emory doctoral student in comparative literature, began working for the Beckett Letters Project in 2006 as an undergraduate at The American University in Paris.

"Beckett is the most abstract of authors," Steyn notes. "His landscapes could be anywhere, his characters could be anyone."

The Beckett Letters Project exemplifies Emory's core mission of fostering sustained intellectual effort, says Vice President and Secretary of the University Rosemary Magee.

"Over time, this work will result in a much deeper grasp of Samuel Beckett as a thinker and artist as he came to understand himself in conversation with a wider literary and scholarly community," she says. "Moreover, it will continue to inform our larger understanding of the impulses and processes that lead to remarkable creativity."