What's the Big Idea?

16 Discoveries That Could Save (Or At Least Change) Your Life

More Than a Band-Aid for Alzheimer's

Most treatments for Alzheimer's disease can only address its symptoms. But associate professor of neurology James Lah is leading a team of researchers in several late-stage clinical trials testing promising disease-modifying therapies. Emory is one of twelve universities participating in a nationwide study on the effectiveness of an experimental medication, CERE-110, the first gene therapy clinical trial for Alzheimer's. CERE-110 seeks to prevent or slow the death of brain cells in Alzheimer's patients by delivering a protein called nerve growth factor (NGF) to the affected area of the brain. NGF nourishes a specific population of cells that deteriorate in Alzheimer's—cells that play a vital role in memory and cognitive function. Lah and Allan Levey, neurology professor and director of the Emory Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (ADRC), also are involved in research that could lead to a vaccine for Alzheimer's and a new method for early detection. The ADRC is one of thirty-two active centers in the nation supported by the NIH.

Heart of the Matter

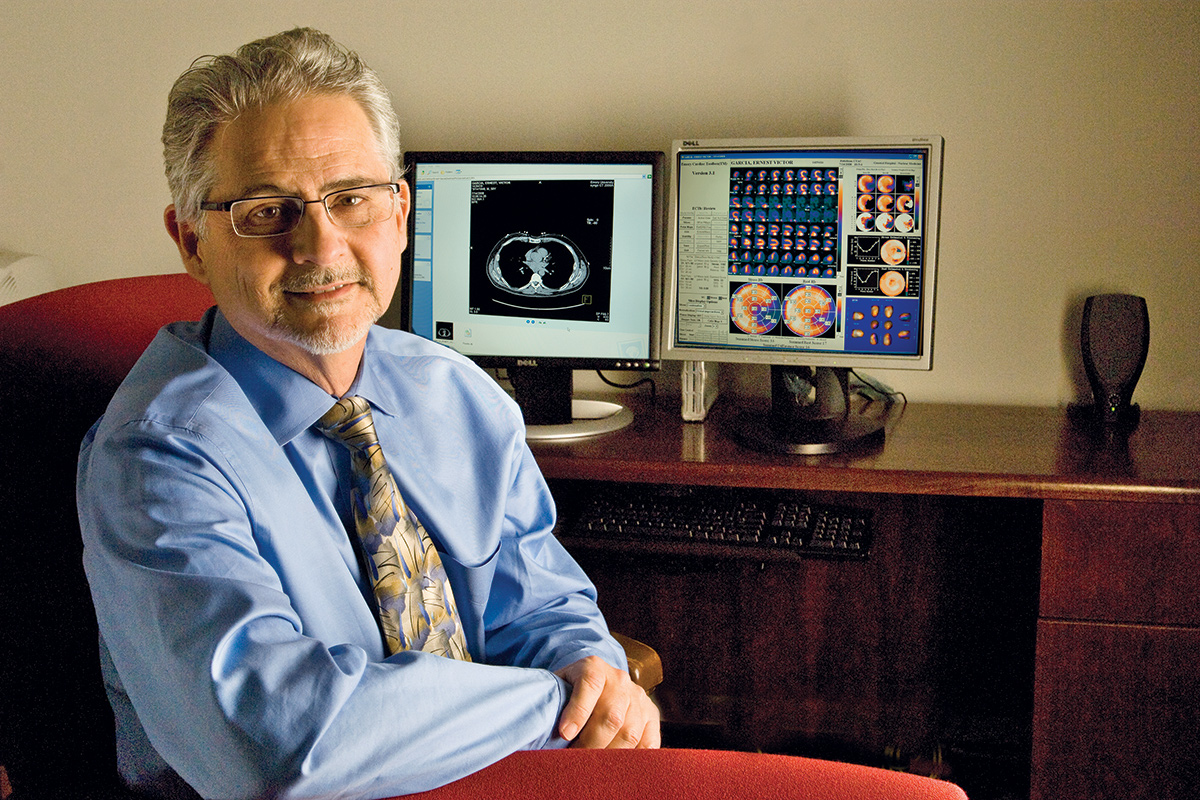

Creator to Consumer: Garcia credits his Cardiac Toolbox invention with saving his own life.

Ann Borden

Heart attacks are the leading cause of death in the US, and many strike without warning.

But a software program known as the Emory Cardiac Toolbox can display a three-dimensional image of a patient's heart, allowing doctors to determine blood flow and efficiency. Developed by Ernest Garcia, professor of radiology in the School of Medicine, the software is one of the most widely applied cardiac imaging systems in the world.

The latest addition to the toolbox allows physicians to more accurately diagnose and treat heart failure.

"In particular, it helps with predicting which patients are going to benefit from specific treatments," Garcia says. "One treatment that is becoming more widespread these days is cardiac resynchronization therapy. Just by using the software and analyzing how the heart beats, we can see how synchronized it is. And if it's not synchronized, we can now predict how well it would improve with resynchronization therapy, a method of restoring the correct mechanical sequence of heart contractions in patients with an irregular heartbeat."

Garcia, who credits his invention with saving his own life, says the most fundamental question the software addresses is whether a patient has coronary artery disease.

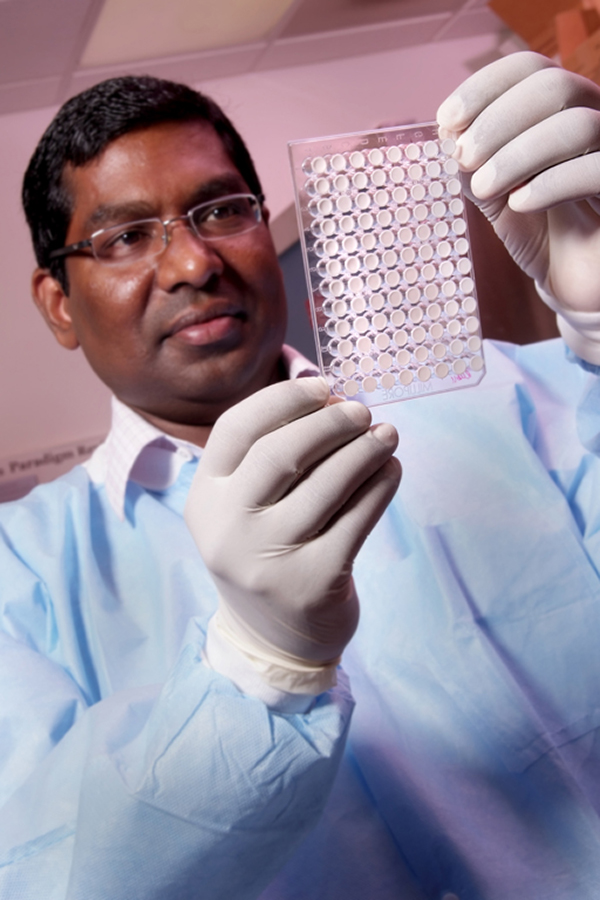

Want a New Drug? Look to Emory

Kay Hinton

Created three years ago, the Emory Institute for Drug Discovery is one of the first and largest of its kind, partnering with small biotech labs, pharmaceutical companies, non-governmental organizations, and foundations in its quest to bring new medicines to market. A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that Emory is the fourth-largest contributor among US public research institutions to the discovery of new drugs and vaccines—ranking behind the National Institutes of Health, the University of California system, and Memorial Sloan-Kettering.

The seven products that landed Emory on the list include HIV/AIDS drugs lamivudine (3TC) and emtricitabine (FTC), discovered by Emory scientists Dennis Liotta and Raymond Schinazi and their former colleague Woo-Baeg Choi. These two drugs are among the most commonly used and most successful HIV/AIDS drugs in the world, taken in some form by more than 94 percent of US patients on therapy and by thousands more globally.

During the past two decades, through the Office of Technology Transfer (OTT), Emory has launched fifty-one startup companies and received more than $788 million in licensing revenues from drugs, diagnostics, devices, and consumer products. More than fifty products are in various stages of development or regulatory approval.

Emory funnels a large portion of the funds from these successes back into a range of programs in research and science education.

Mouse Models

brainstorming: Mice may help us understand how Parkinson's develops.

Bryan Meltz

Gary Miller, a neurotoxicologist and professor in the Rollins School of Public Health, genetically engineered mice to have flaws in their dopamine systems that led them to exhibit symptoms of Parkinson's disease—tremor, stiffness, and slow movements, as well as nonmotor symptoms such as digestive problems and depression. Their brains are providing clues to Parkinson's and how environmental toxins might speed up its progression. Miller will use the mouse models to develop biomarkers of exposure, risk, and early disease, as well as to test whether a promising new brain-protective compound (from the family of flavonoids found in fruits and vegetables), discovered by pathologist Keqiang Ke and colleagues, can restore function to a damaged dopamine system.

Rx for Fragile X?

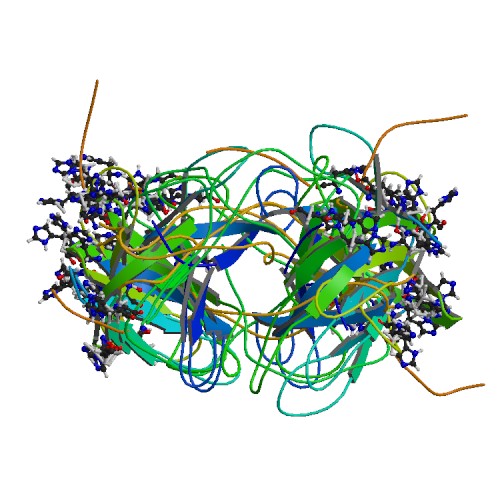

protein promise: A clinical study of a drug that helps boost production of this protein, FMRP, is now being conducted in thirty-two adult participants with fragile X syndrome.

Protein Data Bank

For nearly three decades, Emory scientists have been inching back the curtain on the complex disorder fragile X syndrome, the most common inherited cause of intellectual disability.

In 1991, Stephen Warren, W. P. Timmie Professor and chair of the Department of Human Genetics, led a team that discovered the mutated gene on the X chromosome. Researchers here helped develop a screening test for fragile X and have been studying it ever since, but there has been no treatment.

Now Emory is participating, along with four other medical centers, in a phase II clinical trial testing targeted drug therapy for fragile X syndrome. Warren and others have learned that the genetic mutation of fragile X inhibits the production of a protein, FMRP, that regulates the amount of other proteins produced in the brain. The absence of this protein leads to the overproduction of synaptic proteins triggered by mGluR5 activity, a glutamate receptor that is part of the brain's signaling mechanism. This results in the tangle of learning and behavior problems of fragile X syndrome.

"The drug we are testing is an mGluR5 antagonist, which puts a brake on the mGluR5 activity and may improve learning and cognition," says Emory geneticist Jeannie Visootsak, assistant professor of human genetics and principal investigator of the study. "In mouse and fruit fly models, we were able to improve cognition with an mGluR5 antagonist."

Fragile X syndrome affects about one in four thousand men and one in eight thousand women in the US, in addition to many more carriers of the mutation.

A Light Touch

Serqet, a new, light-activated, antibacterial and antiviral coating that can be applied to respirator masks, surgical masks, cleaning wipes, and dishwashing towels, was developed by Professor of Microbiology and Immunology Gordon Churchward of Emory and Stephen Michelsen at North Carolina State University. The coating produces singlet oxygen, a broad-spectrum antibacterial and antiviral agent, when exposed to light. Singlet oxygen inactivates or eliminates viruses and does not allow any odor or bacteria to grow. The treated item works wet or dry, will continue to be activated by light for up to three months, and can be washed up to ten times.

Treating Incontinence

After experimenting with pig bladders on their kitchen table, father and son research team Niall Galloway, associate professor of urology, and James Galloway 99OX 01C, a physician currently working with the OTT, came up with a prototype for the Periuretheral Injection Technology for treating incontinence, a problem for more than 13 million Americans (twice as many women as men).

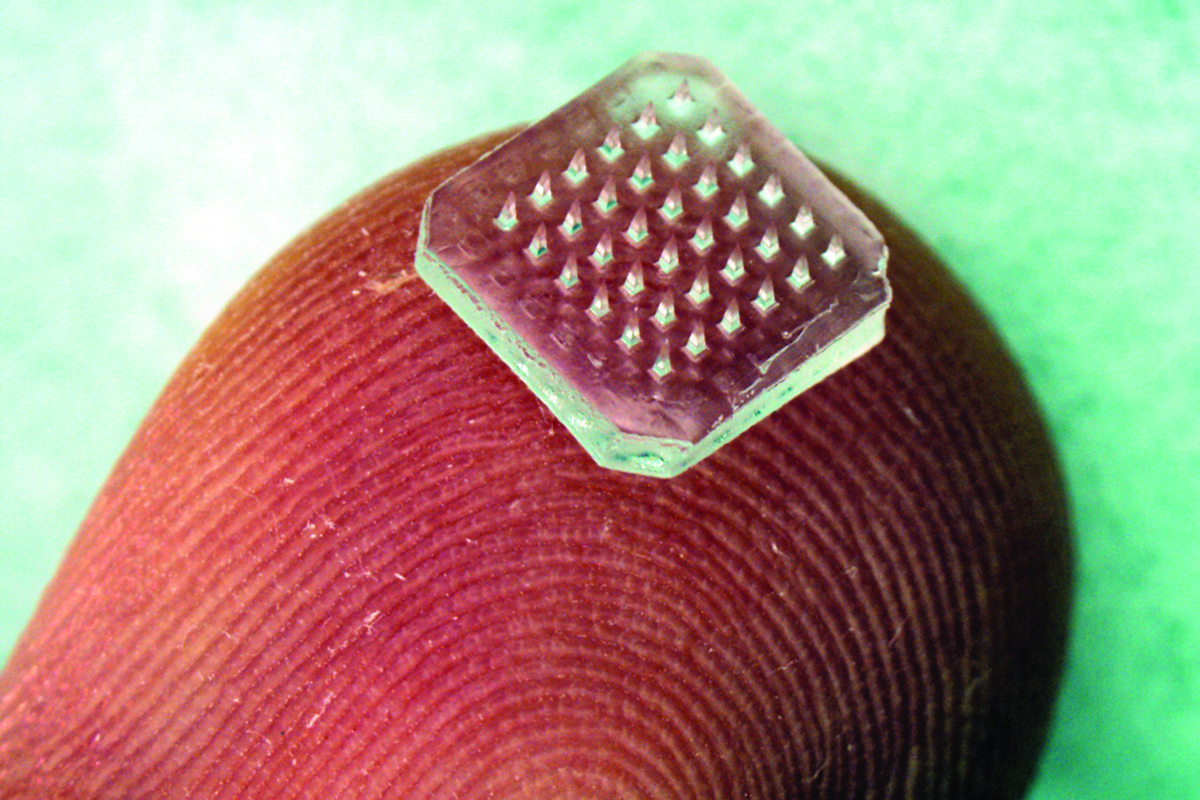

Disappearing Needles

Courtesy Holly Korschun

Let's face it, no one likes to get shots. But a new vaccine-delivery patch based on hundreds of microscopic needles that dissolve into the skin could allow people without medical training to painlessly administer vaccines—while providing better immunization against diseases like flu.

Patches containing micron-scale needles that carry vaccine with them as they dissolve into the skin could simplify immunization by eliminating the use of hypodermic needles—and their "sharps" disposal and reuse concerns. Applied easily to the skin, the microneedle patches could allow self-administration of vaccine during pandemics and simplify large-scale immunization programs in developing nations.

A study in mice conducted by researchers from Emory and Georgia Tech is believed to be the first to evaluate the immunization benefits of dissolving microneedles. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

"The skin is a particularly attractive site for immunization because it contains an abundance of the types of cells that are important in generating immune responses to vaccines," says Richard Compans, professor of microbiology and immunology at Emory University School of Medicine.

Critical Factor

A new treatment for hemophilia A, caused by a lack of blood clotting factor VIII, has been developed by Professor of Pediatrics Pete Lollar, director of hemostasis research at Children's Healthcare of Atlanta.

OBI-1, a special form of factor VIII, is still in clinical testing, but already it has saved a life. The first patient to enroll in the phase III clinical trial at Indiana Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center last November had severe, uncontrolled hemorrhaging due to what appeared to be acquired hemophilia. Through treatment with OBI-1, the bleeding was brought under control.

Unlike people with inherited hemophilia, those with acquired hemophilia don't have a history of bleeding episodes, so the first can be dangerously unexpected. The disorder takes hold when the immune system, for reasons unknown, starts to make antibodies against the person's own clotting factor VIII. OBI-1 is less of a red flag to the immune system, which allows treatment of patients who don't benefit from standard clotting factor VIII because of the presence of auto-antibodies.

Eye See

Emory is exploring oxidative stress management as a treatment for eye diseases. Two classes of NADPH oxidase inhibitors are promising treatments for eye conditions such as the dry form of age-related macular degeneration, particularly the late stage of this condition (geographic atrophy).

Good News for the Blues?

targeted treatment: The key to deep brain stimulation was determining which part of the brain to activate.

Jack Kearse

By pioneering the use of deep brain stimulation (DBS) to treat depression, Helen Mayberg, the Dorothy C. Fuqua Chair for Psychiatric Neuroimaging and Therapeutics, is helping some intractably depressed patients in dramatic ways.

While it can take months for patients to respond to antidepressants or psychotherapy, Mayberg and her team were stunned when some deep brain stimulation patients reported an immediate lifting of their symptoms. "Patients described a sudden disappearance of something negative: a sense of intense calm and relief, a clearing of mental heaviness, the disappearance of a void, the fading of a burrowing dread in the pit of the stomach," she says.

Even more promising, more than half of the patients emerged from their depression and remained well four years later. DBS has been used to treat a variety of neurological disorders, including epilepsy, Parkinson's, and dystonia, but never—until now—depression.

Kinder, Gentler Antirejection Drugs

Transplant recipients have to take lifelong immunosuppresant drugs, which have numerous damaging side effects. But Emory scientists have been working to create more effective and less toxic antirejection drugs, one of which—belatacept—is nearing possible FDA approval.

Whitehead Professor of Medicine Christian Larsen 80C 84M 91R, director of the Emory Transplant Center, says that belatacept preserves kidney function while preventing graft rejection better than the standard drug, cyclosporine.

"Belatacept is different," Larsen says. "It blocks the immune system, but does so in a selective way."

Don't Let the Name 'Programmed Death' Scare You

double trouble: Rama Amara believes that PD-1 could boost both antiviral cells and antibody response to HIV.

Jack Kearse

Could suppressing a little molecule known as PD-1 slow HIV from turning into full-blown AIDS?

Recent research suggests that a boost to the immune system, combined with medication, could send a strong holding signal to HIV for years. Last year, the Concerned Parents for AIDS Research, a New York–based charity, contributed $250,000 to the Emory Vaccine Center—a seed grant that supported collaboration between the lab of Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar Rafi Ahmed, who directs the center, and researchers at Harvard.

That work has blossomed into a $13 million NIH-funded collaboration among several universities aimed at understanding how the immune system is tricked by chronic infections such as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C.

In the journal Nature, scientists described what appears to be an attractive target for HIV therapy: the molecule known as programmed death-1. PD-1 is an immune system receptor that is able to hamper immune responses during chronic infections. Treating monkeys infected by HIV's cousin, SIV, with an antibody against PD-1 allowed the animals to fend off the virus for several months.

"I didn't think that the results from primates would be so strong," says Rama Amara, an Emory researcher at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center who works with Ahmed and performed the monkey studies with Ahmed. "They really blew me away."

A potential clue as to why these results were so strong lies in the way HIV attacks the immune system, Amara says. HIV attaches to CD4+ or "helper" T cells, the white blood cells that initiate the body's response to invading microorganisms.

Previous experimental therapies focused on raising the levels of CD4+ T cells in infected people because patients appear to become more vulnerable to opportunistic infections when levels of the cells drop. But there's a catch. "If you do something to make CD4+ T cells healthier, you could also be giving the virus more targets," says Amara.

Blocking PD-1 may turn out to be a more balanced approach because PD-1 dampens more than one arm of the immune system, Amara says. In SIV-infected monkeys, blocking PD-1 increased both antibody-producing B cells (which protect cells from infection) and "killer" T cells (which clear virus-infected cells from the body) that protected target CD4+ T cells and pushed HIV levels down in a sustained way for months in some animals.

No More Flu?

Scientists at Emory and the University of Chicago discovered that the 2009 H1N1 flu virus provides excellent antibody protection. This may be a milestone discovery in the search for a universal flu vaccine.

Researchers took blood samples from patients infected with the 2009 H1N1 strain and developed antibodies—some of which were broadly effective and could provide protection from the H1N1 viruses that circulated during the past ten years, in addition to the 1918 pandemic flu virus and even bird flu. The antibodies protected mice from a lethal viral dose, even sixty hours post-infection.

The first author of the research, published online in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, is Jens Wrammert, assistant professor of microbiology and immunology at the School of Medicine.

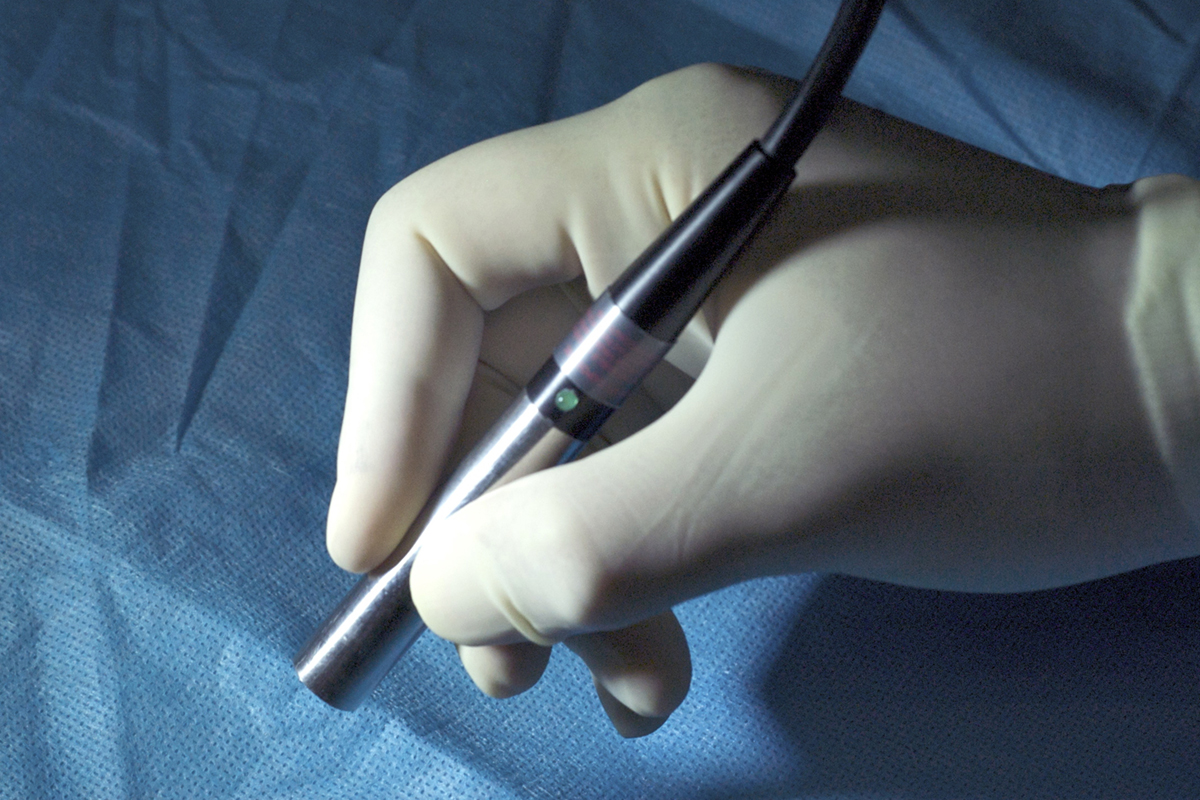

Surgical Precision

Office of Technology Transfer

More than 40 percent of cancer patients who have surgery leave the operating room with cancer cells remaining in their bodies. But a handheld spectroscopic device invented at the Emory/Georgia Tech NIH Center for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence was designed to improve those odds by helping surgeons to better identify the edges of tumors and completely excise them.

Shuming Nie, a professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Emory and Georgia Tech, and colleagues developed the SpectroPen, named a top medical innovation of 2010 by the Georgia Research Alliance.

The SpectroPen combines a near-infrared laser and a spectrometer, and can detect tumors through the use of markers such as fluorescent dyes and scattered light from tiny gold particles. These particles are coupled with a reporter dye and an antibody that sticks to molecules on tumor cells more than to normal cells. "Because SpectroPen can identify tumors with accuracy on the cellular scale," says OTT licensing associate Chris Paschall, "the device has the potential to revolutionize oncological diagnosis, surgery, and treatment."

A Clearer Picture

New molecular imaging software makes attacks on invading cancer cells more accurate and effective, providing patient-tailored treatments. Velocity Medical Solutions, an Emory start-up founded in 2004 at Emory by radiation oncologists Tim Fox and Ian Crocker, produces Velocity AI, which blends cancer images into one high-quality, 3-D-like visual that provides a better look at a tumor's actual boundaries.