As the Circle of Survivors Shrinks, a Way to Remember

A book by Deborah E. Lipstadt marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Eichmann trial

Getty Images

What happens when a scrupulous historian, trained never to cross the double line separating observer from participant, herself becomes part of history? Ask Deborah Lipstadt.

The Eichmann Trial, by Deborah E. Lipstadt; Hardcover, 272 pp.; Nextbook/Schocken $24.95

When editor Jonathan Rosen approached Lipstadt—the Dorot Professor of Modern Jewish and Holocaust Studies at Emory—to do a book associated with the fiftieth anniversary of the Adolf Eichmann trial, she demurred.

She already had written her own courtroom memoir and was not particularly intrigued by the Eichmann case. But Rosen countered, “You’re the one to write it. Your trial [Irving v. Lipstadt, in which she prevailed against Holocaust denier David Irving’s libel charges in 2000] is now considered in a line with the Nuremberg and Eichmann trials. Your voice is important.”

The power of voice was the very thing that made the Eichmann trial a watershed moment in history. “One by one by one,” says Lipstadt, these survivors of the camps—“young people in their thirties and forties who had stitched their lives back together”—faced one of the chief operating officers of the Final Solution in a Jerusalem courtroom beginning in spring 1960.

After the war, survivors had been speaking out—in public settings and books. “It wasn’t they who had been silent,” she notes; “we hadn’t been listening.” Never again, though, would a war-crimes trial proceed without the voice of the victim.

The story of Eichmann’s capture in Argentina, kidnapped by the Israeli Mossad as he stepped off a bus coming from work, captured world attention. Lipstadt’s book, The Eichmann Trial, opens with an account of what was expected to be “a run-of-the-mill budget debate” in the Israeli parliament. Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s two–sentence announcement left the Knesset, and the larger world community, stunned. In this “dramatic understatement,” as the New York Times called it, Ben-Gurion said:

I have to inform the Knesset that a short time ago one of the great Nazi war criminals, Adolf Eichmann, the man responsible with the Nazi leaders for what they called the Final Solution, which is the annihilation of six million European Jews, was discovered by Israel security services. Adolf Eichmann is already under arrest in Israel and will be placed on trial shortly under the terms of the law for the trial of Nazis and their collaborators.

The line of descent among the three trials is real. For instance, Lipstadt’s libel trial was responsible for getting Eichmann’s memoir, written during his imprisonment and under seal by the state of Israel, released into the public domain. When it arrived in time for her lawyer’s closing arguments, she describes the now-familiar mixture of scholarly excitement and human revulsion that has come with access to such documents throughout her career.

On the day of our interview, she opened a file drawer and showed me a Nazi document signed by Heinrich Himmler. It lists the number of “bandits, suspects, partisan helpers, and Jews” who were killed between September 1 and December 1, 1942. For the Jews, the number is a staggering 363,211. The document is set in “the Führer font,” a large face chosen so that Hitler could read about the destruction without the inconvenience of putting on his glasses.

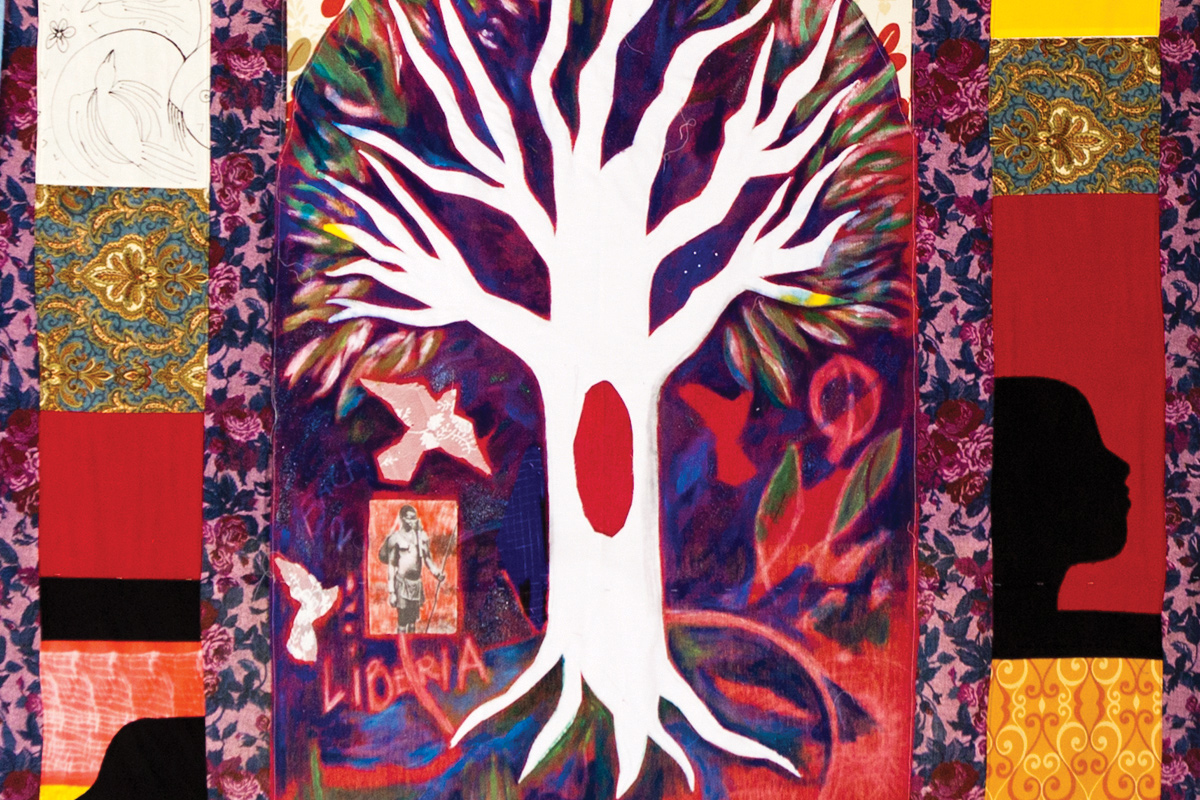

Echoes: Sharing the voices of Holocaust survivors and witnesses at the Eichmann trial, says Deborah Lipstadt, encourages survivors of modern genocides to speak out.

Ann Borden

She takes famed Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal down several pegs (he inappropriately took partial credit for the Eichmann capture) and deals, as every historian of the trial must, with the legacy of Hannah Arendt, whose Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil stirred such strong reaction. Had Arendt fallen into a type that was talked about then, the self-hating Jew? Lipstadt offers a nuanced portrait of Arendt. “She made some terrible mistakes, was glib, and uttered statements that weren’t historically correct,” she says. “She was brutal at times in her language, but she said many important things that have gotten lost in the cacophony of often well-deserved criticism that was directed at her. Hers is a book that won’t go away.”

In the end, Lipstadt points to several salutary effects of writing the book. First, the Eichmann trial became the foundation for Holocaust studies. “It is fascinating to go back to it,” she says, “like looking at the roots of my field.”

Most important to her is that the book provides contemporary sufferers of genocide a way to describe their experience. Several years ago, Lipstadt attended a conference at Yad Vashem—the center for documentation and commemoration of the Holocaust—and talked with young Rwandans, one of whom told her: “I want to tell my story and help my fellow Rwanda survivors tell theirs. Just like the Holocaust survivors, I want people to listen to me as they listen to them.” In her book’s final line, Lipstadt writes, “This may be the most enduring legacy of what occurred in Jerusalem in 1961.”