Soul Food

Adam Richman finds his way to America's heart through its stomach.

Sure, the man can eat.

As the host of the top-rated Travel Channel show Man vs. Food, Adam Richman 96C has faced food challenges around the country, from buckets of scorching chicken wings to piles of loaded nachos to pizzas the size of car tires. By his estimate, his success rate is an impressive 70 percent.

So, yeah, he can eat all right. But the real Richman, the one barely visible behind the twelve-pound burger and the five malted milkshakes, is about more than sheer volume. He loves food, savors flavor, exalts taste and texture, waxes lyrical about ingredients and technique.

A veteran of the restaurant industry, where he hustled his way up to sous chef, Richman can command a kitchen and tell the difference between thyme and tarragon. He brings that experience to Man vs. Food and its new format, Man vs. Food Nation—along with an MFA from the Yale School of Drama, which he pursued after graduating from Emory with a bachelor’s in international studies.

Few people can claim to have the perfect job like Adam Richman can. True story: in 2007, he was between acting jobs and working at Madison Square Garden when he read a self-help book called The Renaissance Soul, aimed at helping people pursue both passions and success. One of the key components of the book was an exercise in which you work backwards from your interests to discover the best job for you. Guess what Richman’s was? Yep, hosting a food TV show.

“Coming out of Yale acting school doesn’t give you a direct career matriculation like a law or medical degree,” Richman says. “It’s easy to get esoteric in an arts career and tell yourself you’re preserving some BS artistic integrity, but artistic integrity doesn’t keep the lights on. Many times you want to give up the struggle. But it’s like when you’re waiting at the subway station and you really just want to take the stairs and walk, but you know the second you do, the train will come.”

Richman’s train came three days after he finished The Renaissance Soul, in the form of an email from an agent at Yale saying the Travel Channel was looking for someone to host a food show that would roam the country spotlighting regional cuisine.

“I launched myself at it, just knowing that was what I wanted and needed,” Richman says.

It’s not a stretch to argue that Richman really started to pursue his dual passions—acting and eating—at Emory, which he chose for a combination of factors, including generous financial aid and the novelty of the South.

A native New Yorker, Richman experienced epic culture shock when he arrived in Atlanta. “It was difficult at first,” he admits. “I was a kid from Brooklyn, and Atlanta was going to be a change. I wanted that. But everything from the way I talked to the music and drinks I liked was different from everyone I met. It was pretty profound. But then I came to embrace it.”

Richman went through a couple of shattering break-ups as a student, and one of the things he did in response was buy a fancy leather-bound Moleskine notebook in which to write, he says, “angst-ridden, black-turtleneck, clove-cigarette-smoking college poetry.” Instead, he wandered into Virginia’s, a cozy restaurant tucked away on a residential street in the Virginia Highland neighborhood (gone now, sadly), and started writing about it.

“Virginia’s was like this little jewel, it was incredible, and after a while I realized I was writing about the whole experience and not just the restaurant,” Richman says.

It was the beginning of a series of food journals that Richman has continued ever since. “After a while,” he says, “friends started to use me as a resource when their parents came into town and they wanted to go to dinner. Eventually I took a step back and realized I had a snapshot of my life as well as Atlanta food.”

When it came to Southern fare, Richman warmed to it like peaches in the Georgia sun, seeking out local haunts and regional specialties. He doesn’t particularly like certain favorites like ham or deep-fried foods, “but collard greens, corn pudding, banana pudding, you can’t beat those,” he says. “And of course, well-made fried chicken and lord knows, proper Southern barbecue, that’s some of the best.”

Richman started at Emory premed, but got burned out with the science course load and changed his major to international studies. If he could do it over, he says, he’d major in creative writing; his first book, America the Edible: A Hungry History, from Sea to Dining Sea, was published last fall. On the other hand, he says his study of other cultures helped to broaden his knowledge of world cuisine.

He got involved with Theater Emory on a five-dollar bet. A fraternity brother saw him perform in a sketch and put up five bucks if Richman would audition for an Emory play. Never (ever) one to lose a bet, Richman went on to act in productions including Teggoni, The Restoration Project, and Superfly.

“He was a great, garrulous guy,” says Vincent Murphy, professor and director of theater studies. “He was kind of wild, so it’s not surprising to me that he ended up on Man vs. Food.”

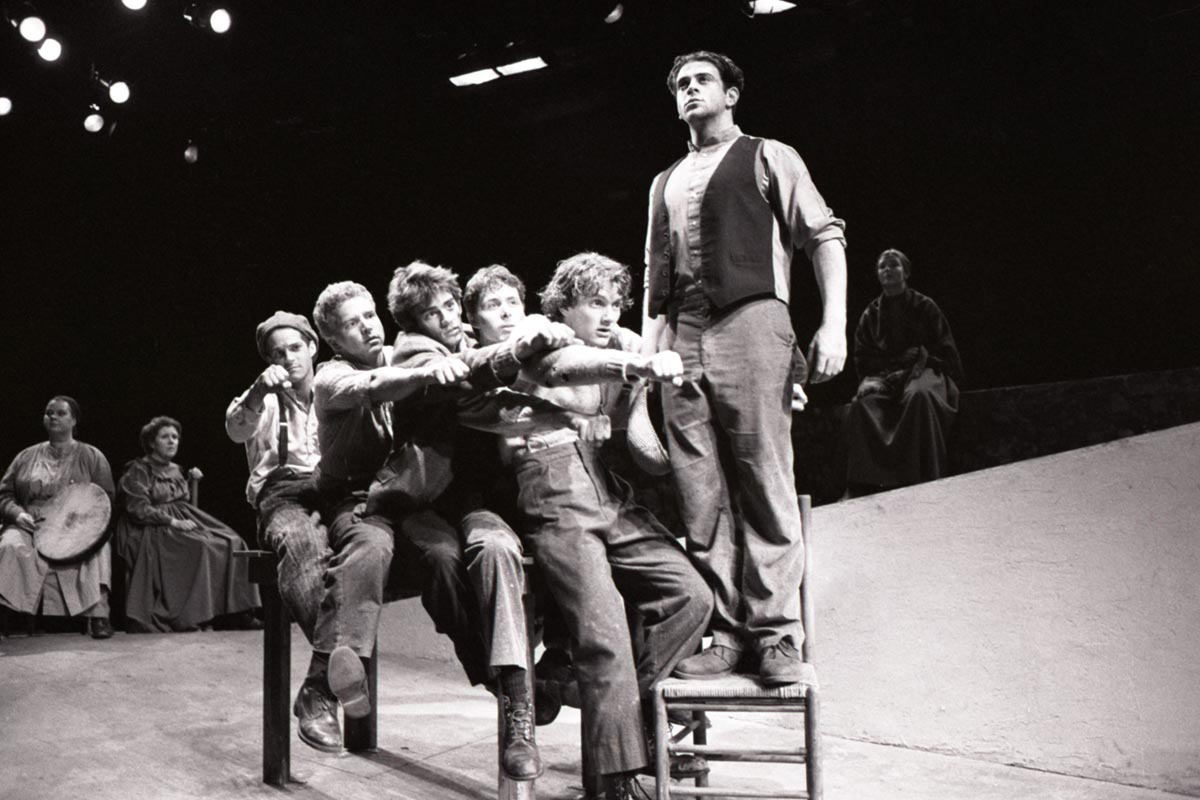

“Adam is indelibly etched in my memory as a character in a play I wrote and directed, American Wake, which imagined the night-long send-off party given four young immigrants on the eve of their departure for America early in the twentieth century,” says Tim McDonough, associate professor of theater studies. “Adam played Gerry, the only character in the play directly drawn from a cousin of mine in Ireland. And like my cousin, Adam was the unofficial mayor of the community of actors who came together for this play—a kind of glue and stabilizer and peacemaker. Adam ended up that summer in Ireland and visited my cousin’s pub, which is emblematic of how deeply he felt what he was working on.”

After graduating from Emory, Richman joined Murphy to do an unpaid apprenticeship at the Actors Theater of Louisville. His father died unexpectedly during that stint, plunging Richman into dark doubts about his choices and his future. “Emory is a terrific school, and here I was, in 1996 with a burgeoning Internet industry and all these resources, you’d think I would join the corporate world,” he says. “I was like, I’m not focusing on what I should. But I went back and finished the apprenticeship.”

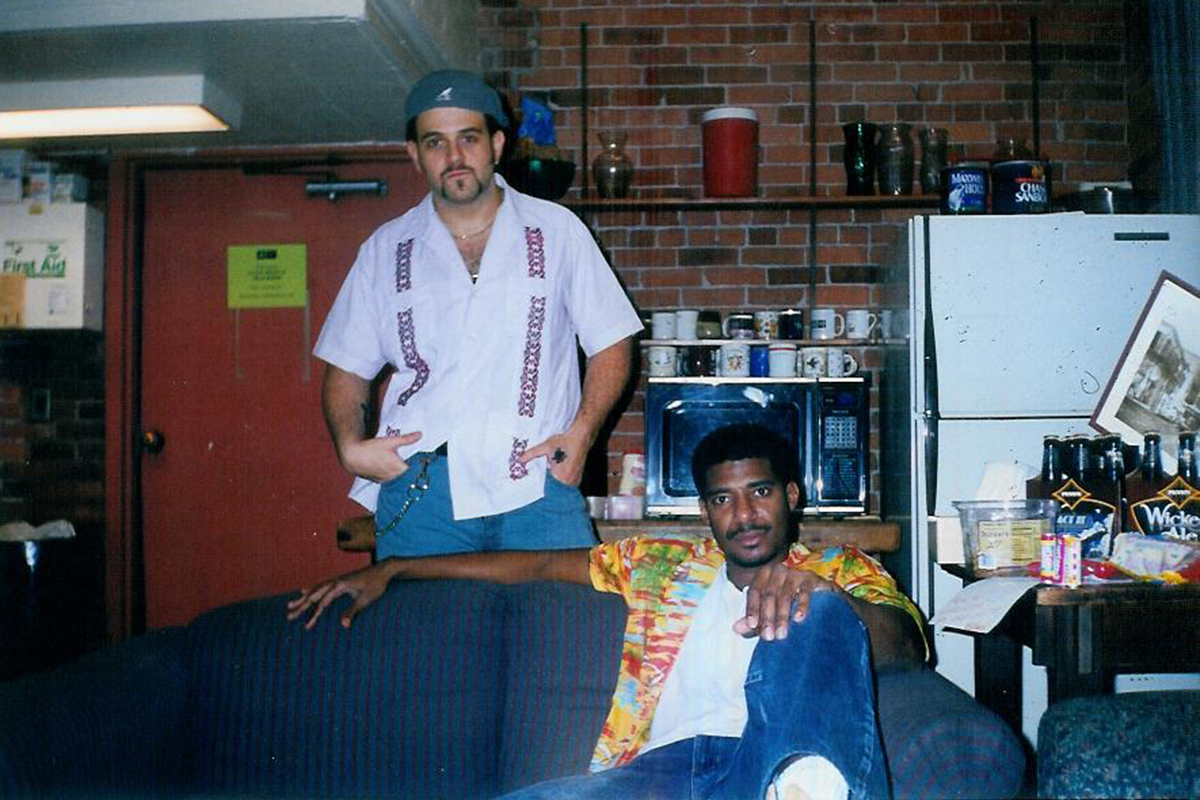

At Yale, Richman threw himself into the program, even spending late-night hours after classes rehearsing for cabaret theater productions that the drama students mounted just for fun. A close friend, Billy Eugene Jones, knows Richman as a smart, funny, and wildly versatile actor who dove headlong into every project and performance. “He is about the most all-around talented person I know,” says Jones.

Christopher Bayes, a comedy instructor, recalls, “Adam always seemed game for anything and ready to attack the work. I never imagined that he would find a career as a TV personality, but it makes so much sense. He is so uniquely himself, generous and open and always looking for some fun.”

Richman makes fronting Man vs. Food look easy, but he claims to call on every ounce of his training at Emory and Yale to maintain the show’s natural, irreverent spirit and fast-paced energy. “There is an element of sheer camera comportment that you have to learn, pushing out as much text as I do,” he says. “That is all breath support and vocal training. Even through the food challenges when I’m screaming my head off, I’m very reliant on my acting training.”

Richman trains in a different way for the challenges, the climax of each episode, when he attempts to surmount some signature dish breathtakingly daunting in size, spice, richness, or all three. To prepare, Richman fasts to cleanse his system, and also does leg workouts and sprints to rev his metabolism. “The idea,” he says, “is to come in empty and very hungry.”

Usually the challenges are established gastric gauntlets that have been attempted by generations of hopefuls before Richman. The element of local legend gives him a natural point of connection with the chefs and customers, who crowd around to cheer him on.

Richman has tackled a seventy-two-ounce steak in beef-loving Amarillo, Texas; the saucy Wing King Challenge in Boulder, Colorado; a towering Dagwood sandwich in Columbus, Ohio; the Kodiac Arrest—featuring crab, salmon, and reindeer—in Anchorage, Alaska; and the five-pound Jumboli Stromboli in Butte, Montana. At a press conference following that one, a young fan asked how five pounds of doughy, cheesy stromboli felt in his stomach. “It feels,” Richman replied, “like victory.”

But the man eater has also tasted defeat. Some five hundred contenders have attempted the Crown Candy Five Milkshake Challenge in St. Louis, but only twenty-two managed to slurp them all down. Richman, sadly, was not among them; the first three shakes made an unexpected reappearance, the food challenge equivalent of a knockout in the third round.

When Man vs. Food premiered in late 2008, it brought the Travel Channel its highest ratings ever. Now Man vs. Food Nation’s Facebook page has more than 1.1 million fans and Richman has about 118,000 followers on Twitter. Critics of the show’s premise have pointed to the American obesity pandemic and the lack of adequate food in poor parts of the world, but Richman has always emphasized that the food challenges are meant to be viewed as rare indulgences and not routine choices.

“There seems to be this perception that I don’t care about health, or that somehow if Man vs. Food didn’t exist, neither would hunger,” he says. “But I hope people will see it like I do, an expression of pure, unbridled joy and pleasure in taste, flavor, and fun.”

There have been rumblings among observers that the show has taken a toll on Richman’s health, the real reason for the shift to the new format in Man vs. Food Nation. But Richman is quick to brush them off. “Any spectacle diminishes over time, and if you wait for the audience to say it, you have waited too long,” he says. “We just wanted to keep it fresh.”

The producers, Richman included, also wanted to give the local fans a bigger piece of the pie. In the new program, they are the ones facing the ultimate eat-offs, with Richman urging them on. The role reversal is well in keeping with the show’s heart and soul—the praise of local, indie, one-of-a-kind eateries serving up regional specialties that have attracted a foodie following, much like Richman himself.

“This is a chance to share the opportunity with other people and let them represent their hometowns,” he says. “The best part of the show for me will always be the people, and it’s the locals that make these places iconic and create legends. The focus on the community is going to be tremendous.”