Root Words

As chief editor of the Dictionary of American Regional English, Joan Houston Hall 76PhD leads a grand adventure through American language

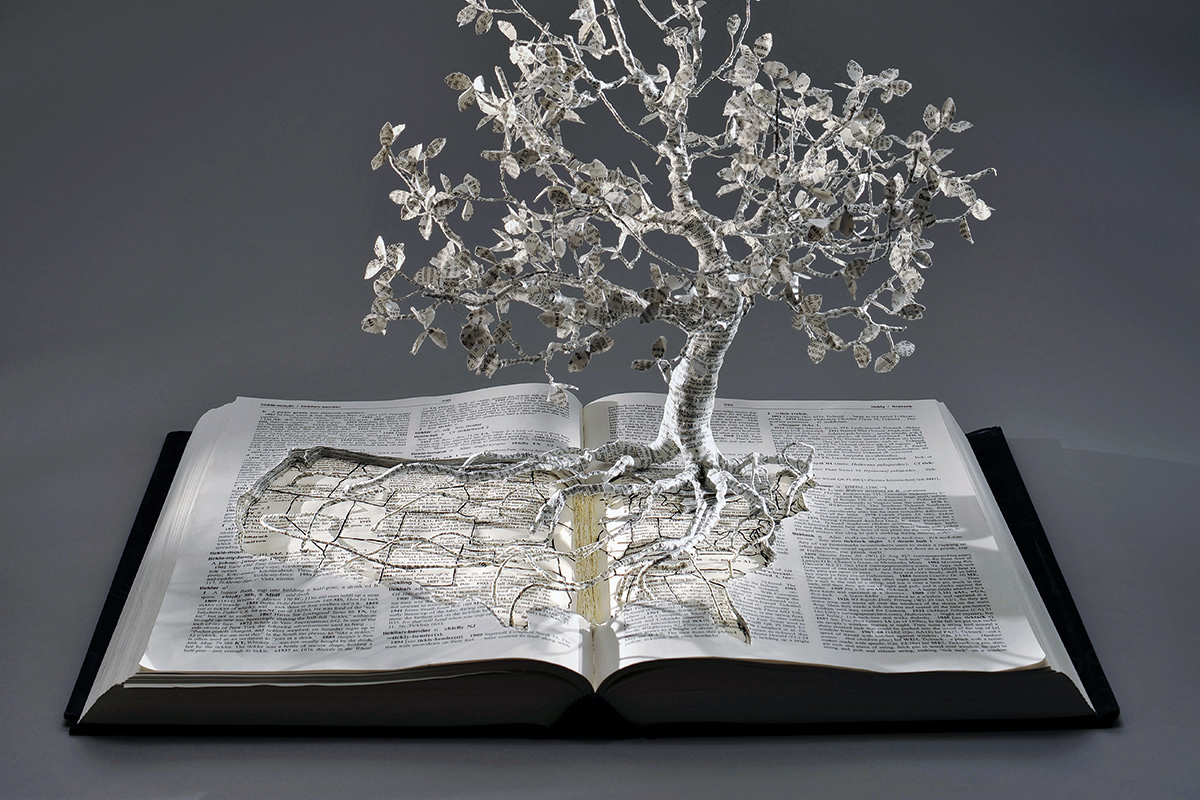

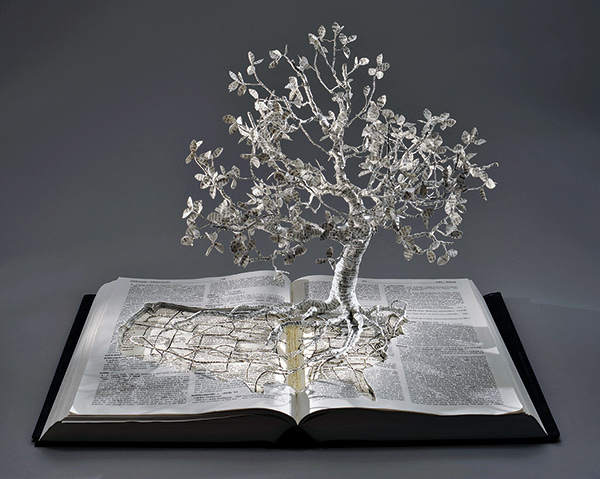

Illustration by Su Blackwell

The next time you go out for lunch, consider walking up to a counter and ordering an oblong sandwich, fried potatoes, and a sweet, carbonated beverage . . . please.

Sure, the server might look at you a little funny. But depending on what part of the country you're in, the sandwich could be a sub, a hoagie, a grinder, a Cuban, a hero, an Italian, or a poor boy; the potatoes could be French fries, home-fried potatoes, or cottage fries; and the beverage could be soda, pop, a soft drink—or, if you're anywhere near Atlanta, just a plain old Coke, thank you.

Deciphering the different dialects of the United States has been the delicate work of Joan Houston Hall 76PhD, chief editor of the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE), since she finished graduate school at Emory and joined the project in 1975. Nearly a half-century in the making, DARE published its much-heralded fifth volume early this year, which reached the end of the alphabet—the final word being zydeco, a style of Cajun music common to Louisiana. (You might also say the dictionary now goes from A to izzard, a phrase meaning from beginning to end, or the epitome of something.)

The latest installment has been showered with praise and attention from linguists, scholars, the media, and logophiles the world over, garnering top stories in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Chronicle of Higher Education, National Public Radio, and virtually every major outlet in the country. The weighty, blue, twelve-hundred-page volume is now making its way to reference libraries everywhere—including Emory's, of course—to join its four equally hefty younger siblings.

Joan Houston Hall 76PhD

Jeff Miller/University of Wisconsin-Madison

In a stroke of serendipity, Volume V made its debut appearance in January at the annual meeting of the American Dialect Society (ADS)—an organization that dates back to 1889 and whose history is deeply entwined with that of DARE.

"The press sent a copy of the final volume to me at the meeting, and everybody was just astounded," Hall says. "I was thrilled, of course."

She wasn't the only one. "When she revealed it to the assembled language scholars, the excitement was palpable," wrote Ben Zimmer, linguist, columnist, and chair of the ADS New Words Committee, in the Boston Globe. "Jesse Sheidlower, editor at large of the Oxford English Dictionary, shared the exultant news on Twitter."

Hall, the DARE research staff—numbering a baker's dozen—at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the dictionary's prestigious board, and other stars of the linguistics field also gathered in Madison in early May for a symposium and a celebration of Volume V. One of the speakers was Michael Adams, associate professor of English at Indiana University and editor of the journal American Speech.

"Touring the Dictionary of American Regional English is a road trip of the mind from sea to shining sea. . . . It speaks with authority about American regional speech and has also captured the popular imagination," Adams wrote in Humanities, the magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities, a primary financial supporter of DARE. "It is a peerless resource for scholars, but at the same time delivers accurate information about regional vocabulary to laypersons who, until DARE, could not count on access to it."

Born in plainspoken Ohio, Hall grew up in San Rafael, California; her mother was formerly a high school English teacher and her father was a chemist. As she and her sister and brother grew older, the whole family relished doing the Double Crostic puzzles in the Saturday Review. "It was really fun to see how much we could answer without going to the reference books, but then there was some joy in that because it gave us a reason to use those books, which we treasured," Hall says.

She also recalls a cross-country family trip for which her father readied them by reading from various histories and books about American places around the dinner table. Thanks to his thorough preparation, when they arrived in Boston, Hall knew that to order a milkshake would only get her wan, flavored milk; instead, she and her sister proudly ordered a frappe, the local term for the thick, creamy indulgence they had in mind—now made more familiar, if not more authentic, by Starbucks's trademarked Frappuccinos.

That sweet taste of an idiomatic term on the tongue made a lasting impression on Hall—one deep enough to lodge the story in her personal narrative. Her early interest in regional words may also have helped guide her decision to major in English at the College of Idaho before coming to Emory to pursue a PhD, also in English, with a concentration in—again—English language.

When Hall arrived as a first-year student in 1968, she was unable to register for the literature courses she wanted in Southern or medieval English because the more senior students had filled them up. Just about the only option left was a class called History of the English Language, taught by Professor Lee Pederson, a linguist who also happened to be engaged in the groundbreaking Dialect Survey of Rural Georgia at the time. His students were required to write three lengthy papers—or, as an alternative, they could do fieldwork, conducting interviews for the survey. With ten papers looming in other classes, Hall opted for the latter.

She couldn't know then that her unexpected connection with Pederson would set her on the path to DARE, Volume V, and eventually the triumphant strains of zydeco. In fact, Pederson was emerging at the very forefront of the field; he had completed doctoral work in 1963 at the University of Chicago with noted linguist Raven I. McDavid Jr., editor of the Linguistic Atlas of the Middle and South Atlantic States and several other books on American language. McDavid encouraged Pederson to pursue a similar effort in the South. When Pederson came to Emory, he was charged with assembling the Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States (LAGS): a colossal, twenty-year project that was still in its early stages when Hall signed on. Similar resources had been created in other parts of the country, including McDavid's atlas and the equally influential Linguistic Atlas of New England, but Pederson was the first to undertake the effort for the South—considered a particularly rich region for the study of language patterns, vocabulary, pronunciation, and grammar.

The Dialect Survey of Rural Georgia was a lengthy research project designed to lay much of the groundwork for LAGS. Pederson, colleagues, and graduate students traveled out to some three hundred rural communities toting bulky, old-school tape recorders and microphones and carefully crafted questionnaires of more than three hundred items. The assignment was to identify four local residents over age sixty-five—two black, two white, and at least one well educated and one poorly educated—and interview them, bringing the recordings back so that Pederson and the team could hear the pronunciations and speech patterns.

"I loved it. It was fascinating," Hall says of the fieldwork. "I knew nothing about the South, and it gave me a chance to see a very different part of Georgia from Atlanta."

A stranger to the South, Hall was also unfamiliar with African American culture and the ways of Georgia communities at the time; for instance, when she would ask for an African American woman as "Mrs. Smith," residents were taken aback, accustomed to calling black people by their first names only. "I found this very strange," Hall says. "It was part of learning about a completely different culture."

Hall recalls interviewing a ninety-four-year-old African American man, a successful farmer with a good deal of land, and taking a brisk, confident approach. "I was thinking of myself as a young professional, out doing very important work," Hall says wryly. She was going through the routine questions—"What do you call a shelf above the fireplace?"—as he regarded her quizzically. Suddenly the farmer leaned forward and drawled, "Now, what's a little girl like you doing so far from her mama?"

Altogether, the LAGS team gathered more than five thousand hours of talk from more than a thousand Georgia residents, which were eventually transcribed and compiled in atlas form. Many of the words had never appeared in any other dictionary. "They are, in fact, new additions to the language, and Pederson is responsible for preserving them from extinction," read a 1981 Emory Magazine cover article on the LAGS project.

"It was very serious work that took up the lives of a dozen people for a number of years," Pederson, now retired, said in a recent phone interview. "It provides a basis for evaluating the speech of this generation. The pronunciation in Shakespeare's works would not be a mystery today if we had a linguistic atlas of that time."

In the late 1960s, LAGS and DARE were like language-hunting locomotives on separate but parallel tracks, both beginning to gather steam. Hall remembers hearing about DARE as an Emory student while working on the Gulf States project; in fact, LAGS would ultimately contribute some 2,400 citations to DARE.

After completing her Emory coursework, Hall went on to get married in 1971 and moved with her husband to Oregon, then Maine. In the spring of 1975, she was still working to finish her dissertation—an analysis of pronunciations in rural southeast Georgia—when her old professor Lee Pederson called. Fred Cassidy, an English professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the chief editor of the sweeping Dictionary of American Regional English, was looking for an assistant editor. Was Hall interested?

Yes, yep, yup, yah, uh huh, yes sirree, Bob. She was.

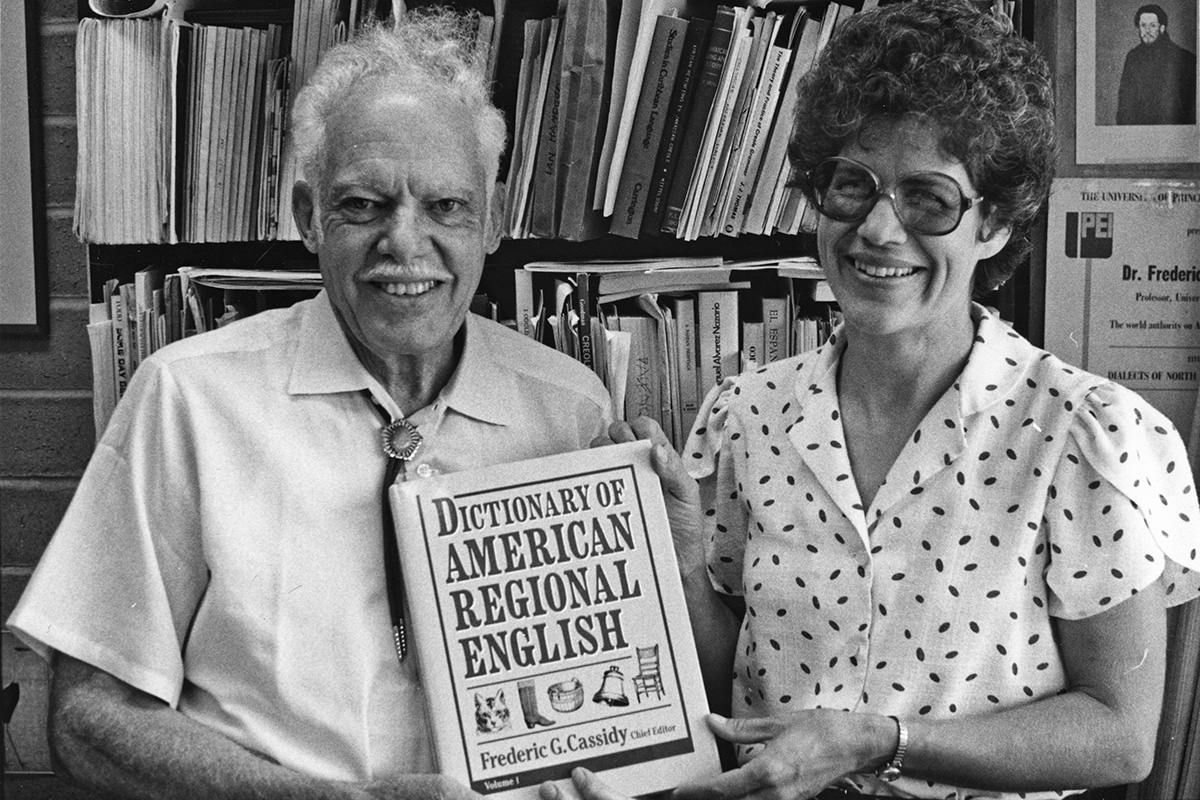

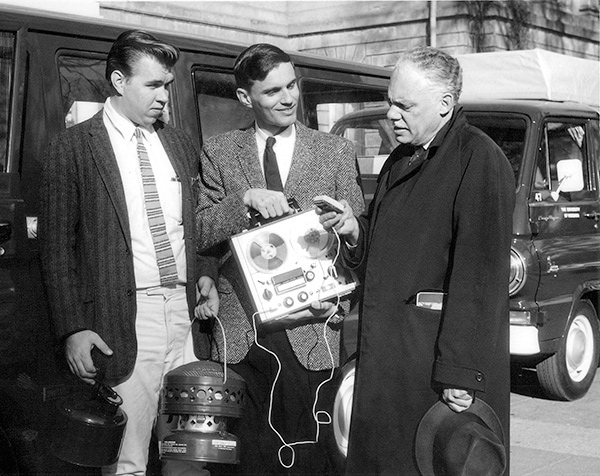

Joan Houston Hall 76PhD joined DARE visionary Fred Cassidy (above right, left) in 1975; Volume I, here proudly displayed, was published a decade later.

Jeffrey Steele

A longtime member of the American Dialect Society, Cassidy was the principal visionary behind DARE. According to the project's website, the idea was batted around in the organization for the first half of the last century, until Cassidy finally brought matters to a head at the society's annual meeting in 1962 by reading a paper titled, "The ADS Dictionary—How Soon?" For answer, the ADS made Cassidy chief editor of the dictionary-to-be.

Cassidy had already begun developing a questionnaire that addressed virtually every subject under the sun—from the names of the most everyday household items to ideas about religion, marriage, and money. The final document totaled more than 1,800 questions. Between 1965 and 1970, a cadre of some eighty field workers, mainly graduate students and a few professors, fanned out to more than a thousand communities around the US in vans known as "word wagons," hunting up natives who were willing to spend a few hours lending their voices to a noble cause—mapping American dialects.

The communities' locations were carefully selected to trace US history and immigration patterns, the driving force behind differences in language. Although some accents may sound stronger than others, Hall says, there is no such thing as neutral speech. "By definition, everybody speaks a dialect," she says. "The sources of the early settlers are probably the most important influence on dialects."

On the East Coast, for instance, English settlers dominated, with many British, Scottish, and Irish immigrants drifting south to work in coal mining towns—their clipped speech shaping today's Appalachian twang, which is distinct from the more languid drawl of the deep South. Meanwhile, the industrial cities of the Northeast also saw a heavy influx of continental Europeans, whose varied languages eventually helped distinguish the English of that region from that spoken in the South and Midwest.

And in Wisconsin, Hall was introduced to words like bakery (not just the shop, but the pastries themselves), rumpelkammer (a junk room), and schnickelfritz (a mischievous little boy), all remnants of the heavy German immigrant influence dating back generations.

Fieldworker Ruth Porter ponders what might be called a skillet, spider, or fry pan, 1965.

University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives

When Hall arrived in Madison in 1975, the fieldwork for DARE had been completed: interviews with 2,777 "informants," 1,843 of which had been recorded, yielding more than two million individual responses to the questions—not to mention thousands of hours of conversational speech. Although the informants remained anonymous, they were identified by geographic location, age, level of education, occupation, race, and gender; all of that information became part of DARE's "List of Informants." More than half of the informants were over age sixty, contributing their knowledge of words used in olden times, before many of the inventions of the twentieth century profoundly changed American society.

The questionnaire responses were fed into a mainframe computer that today would seem like a gargantuan relic from an episode of Star Trek. But Cassidy recognized the early computer's ability both to organize that mountain of data, and to use it to produce the maps that are a hallmark of DARE—maps that are graphically organized by population density rather than US geography, and that reveal where particular words and phrases are used most, least, and not at all.

"Cassidy was perhaps the first lexicographer to integrate computation fully into a dictionary project's production process, first and foremost to manage and manipulate data efficiently and effectively," writes Michael Adams.

While the giant computer was humming along, Hall and the growing team of DARE editors were doing what dictionary editors do: taking the regional terms and searching every possible source for verification and examples of their use. In addition to the maps, another remarkable aspect of DARE is the rich array of sources and information provided for each entry, lending the dictionary what Adams describes as a "homespun texture": editors included the questionnaire responses, identified by informant; both the first known instance and the most recent use of a word; and relevant examples from literature, newspapers, other linguistic atlases, and even personal archives.

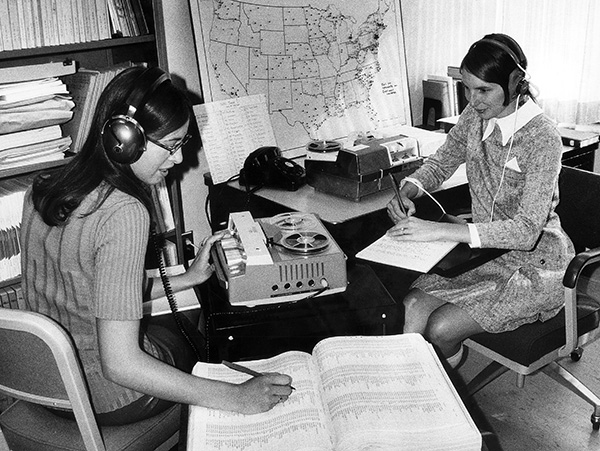

Project assistants Beth Witherell (left) and Jennifer Ellsworth listen to DARE tape recordings, 1971.

University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives

By 1979, Hall was associate editor of DARE, playing a lead role in the hiring, training, and oversight of the editing staff; she also became the coprincipal investigator on major grants. Volume I (the lengthy introduction, and A though C) was published in 1985, ten years after Hall arrived, and publicly welcomed with enthusiasm rivaling that created by the recent Volume V. The next two volumes appeared in 1991 and 1996. When Cassidy died in 2000, Hall was his natural successor as chief editor, having done much of the job in Cassidy's later years.

"Less flamboyant than Cassidy," writes Adams, "she shares his commitment to the highest scholarly standard and has demonstrated the patience and sometimes steely determination necessary to keep a multivolume dictionary project funded and on schedule."

Although DARE is housed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the long-term project and its staff have been funded by a combination of sources over the years—most notably the National Endowment for the Humanities, which has contributed more than $10 million since 1971. Other supporters include the National Science Foundation, private foundations such as the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and individual word lovers. "That's the hardest part," Hall says, "finding funding."

But the value of DARE is not hard to justify. Its users are plentiful, wide-ranging, and often surprising—from linguists and other scholars of words and language, to authors and actors looking to perfect bits of regional dialogue, to even doctors and detectives with mysteries to solve.

Cassidy with fieldworkers Reino Maki (left) and Ben Crane, 1965.

University of Wisconsin-Madison Archives

One of the most famous uses of DARE involved a case of kidnapping in which the perpetrator left a note demanding that the parents leave $10,000 cash in a diaper bag and put it on the "devil strip." A forensic linguist, who was asked to analyze the note, had no idea what the devil strip was, nor could he find it in any traditional dictionary. But a citation in DARE revealed that the term is used in a small part of Ohio, where it means the strip of grass between the sidewalk and the street. By isolating where the kidnapper probably lived, authorities were able to track him down.

Physicians, too, might find it useful to keep DARE handy alongside Gray's Anatomy. Body parts, ailments, and treatments go by all sorts of different names depending on what region of the country they're in. Hall recalls getting an email from a doctor who grew up in Maine, but later found himself practicing in rural Pennsylvania. Confronted with a patient complaining that he had been "riftin' "and had "jags in his leaders," the doctor was baffled; but a quick consultation of DARE clarified that the man had been belching and had pain in the tendons of his neck.

DARE is undoubtedly a vast repository for such rare and endangered utterances—words that may be fading from everyday use and are not cataloged in any other print resource. But Hall is quick to refute the notion that the dictionary is filled with obsolete terms and quaint, outdated phrases. DARE is a living, breathing work, evolving to keep up with language patterns as fast as they change—which is perhaps not as fast as you might think.

"Of course one of the reasons we do this work is to record words that are going out of use," she says. "But it is also to check distributions of contemporary vocabulary. In addition to the earliest known citation, we try to get the latest one we can. In Volume I, which appeared in 1985, some quotes are from 1984; in Volume V, some are from 2011."

The notes of the celebratory zydeco still linger in the air, but there is no time for Hall and the DARE team to get poke-easy or resty (lazy). Next year, Harvard University Press plans to offer a digital version of the dictionary; the maps need to be updated to reflect the 2010 census; and one day, Hall hopes to return to those original one thousand communities (via the Internet) with an updated questionnaire.

"Yes, of course, the language has changed over the thirty-five years since DARE did its fieldwork—it's the nature of language to change," Hall said in a talk at Emory in 2004. "But that doesn't necessarily mean homogenization. I suspect that if we were to ask the same questions today that we asked thirty-five years ago, we would find that many of the regional patterns would still be recognizable, but that they would be less distinct and would have significantly more outliers. At the same time, new patterns would emerge."

Asked if she has a favorite DARE word, you might expect Hall to politely demur. You would be wrong. Her favorite word is bobbasheely, and its place in DARE has a colorful and layered history. It was used across the Southern states, and it means something good.

But if you want to know what, you should find the nearest copy of DARE, Volume I, and look it up.