|

On

a cool,

shining November afternoon, two Secret Service agents wait impassively

behind their sunglasses outside Emory’s Rollins School

of Public Health, speaking periodically into their wrists. Inside,

fifty students taking a class in anthropology and international

health are in their seats early, abuzz with anticipation. At

2 p.m., a gleaming black Chevy Suburban rolls smoothly into

the circular driveway to pull up beside the small, nervously

expectant group gathered on the sidewalk. Former U.S. President

Jimmy Carter, silver-headed and distinguished in a dark suit,

steps out, accompanied by a handful of aides and security. He

graciously shakes hands with Jennifer Hirsch, the assistant

professor whose class he’ll be teaching today, and poses

briefly for a picture, flashing a practiced smile in the bright

sun.

The

scene is not entirely unfamiliar at Emory, but the former president’s

presence still carries a charge that seems to thrill everyone

he encounters. Without appearing to hurry, Carter sets a smart

pace that sends those around him scrambling to keep up. In the

classroom, he is both commanding and compelling, his down-to-business

approach tempered by his mild humor and unmistakable Southern

manner.

Carter

describes for Hirsch’s students the twenty-year-old “marriage”

between Emory and the Carter Center, the organization whose

work has consumed him and his wife, former First Lady Rosalynn

Carter, since shortly after he left the Oval Office in 1981.

Created to promote peace, democracy, and the resolution of conflict

around the world, the center’s mission evolved to also

address massive shortfalls in global health.

“The

greatest needs,” Carter tells this class of potential public

health professionals, “fall directly on the shoulders of

public health. Most choose [this work] because of cultural,

moral, or religious motivations.”

Carter,

a University Distinguished Professor since 1982, says he enjoys

teaching the occasional college class. “I’ve taught

in all the schools at Emory,” he said in a recent interview

with Emory Magazine from his home in Plains, Georgia. “It

has kept me aware of the younger generation, their thoughts

and ideals.”

This

is, however, the first time Carter has appeared at the University

as a Nobel laureate. He won the Nobel Prize for Peace on October

11, 2002, “for his decades of untiring effort to find peaceful

solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and

human rights, and to promote economic and social development.”

Although

Carter had been considered a candidate for the prize since he

negotiated the Camp David Accords in 1978, his recent public

stance on international affairs–including possible U.S.

aggression toward Iraq–also played a part in his winning.

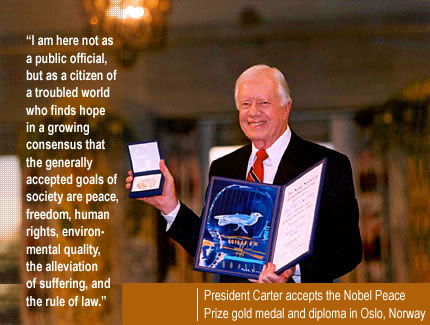

When he accepted the Nobel gold medal in Oslo, Norway, in early

December, Carter repeated the warning that he had issued at

an Emory town hall event just weeks before the prize was announced–that

war, sometimes a necessary evil, is “always an evil, never

a good.”

“I

am here not as a public official,” he said, “but as

a citizen of a troubled world who finds hope in a growing consensus

that the generally accepted goals of society are peace, freedom,

human rights, environmental quality, the alleviation of suffering,

and the rule of law.”

Over

the past two decades, Carter has secured his reputation as the

most effective and accomplished former U.S. president in history.

At seventy-eight, he continues to guide the Carter Center with

a sure hand, clear vision, and legendary drive. Charged with

“waging peace, fighting disease, and building hope,”

the center has helped resolve conflict in developing countries

around the world. Always a leader by example, Carter, along

with Rosalynn and center staff, has personally monitored dozens

of elections around the world to ensure fairness in emerging

democracies. He received the U.N. Prize in the Field of Human

Rights in 1998 for the Carter Center’s worldwide efforts

to preserve and promote human rights.

On

the principle that health is a basic human right, Carter also

has led the center to nearly eradicate the devastating Guinea

worm disease in regions throughout Asia and Africa, reducing

its incidence by 98 percent. Major inroads have been made in

the fight against river blindness, or onchocerciasis, and trachoma

in Africa and Latin America; efforts to combat schistosomiasis

(“snail fever”) and lymphatic filariasis (“elephantiasis”)

are succeeding as well. Agricultural programs aimed at cultivating

self-sufficiency have helped African farmers increase their

productivity by as much as 500 percent.

The

Carters continue to volunteer for Habitat for Humanity for one

week each year, building houses in the U.S. and abroad. Since

his presidency, Carter also has written sixteen books.

In

addition to teaching at Emory periodically and appearing at

town hall events, Carter holds small monthly lunch meetings

with various deans and professors to discuss the linkage between

their programs at Emory and those at the Carter Center. The

Carters also have a private breakfast each month with University

President William M. Chace to talk about developments at the

two institutions.

Because

of Carter’s longstanding ties to Emory as a faculty member,

Carter Center partner, colleague, and friend, leaders across

the University greeted news of his Nobel Prize with shared pride

and pleasure. James T. Laney, who was president of the University

when the Carter Center was founded and helped form the partnership,

says the honor was long overdue. As U.S. ambassador to Korea,

Laney wrote a recommendation to the Nobel committee for Carter

in 1994.

“It

could have come earlier, and it would have been eminently justified,”

Laney says. “But now it is a grand capstone of his life

and career for which we all rejoice.”

“We

have watched for years as this native son of Georgia has, since

his presidency, advanced, in many different ways, a vision of

healthy understanding among the nations and people of the world,”

says Chace, who attended the Nobel ceremonies in Oslo. “He

served his country well as president but he is now being recognized

for all that he has so superbly done since that presidency.”

In

his lecture to Hirsch’s public health class, Carter encapsulates,

as neatly as possible in thirty minutes, these two decades of

Nobel-worthy endeavors. Afterward, when a student asks him how

he prioritizes the conflicting demands and influences he faces

in situations around the globe, he reveals the uncompromising

commitment and moral compassion that have marked his life as

a leader and helped to earn him the honor many consider the

highest in the world.

“One

of the revelations that I have had since I left the White House,”

he says, “is the inseparability of the factors that shape

the quality of human life. Justice . . . peace . . . freedom

. . . the alleviation of suffering. . . . I see it like this:

all are of an equal nature.”

When

class is over, Carter takes his leave with quintessential Southern

graciousness. “Thank you,” he tells the students,

and adds, without a trace of irony: “You have really inspired

me this afternoon.”

When

President Carter

came home to Plains, Georgia, after being defeated for a second

term in 1980, his future was uncertain. As

he began to look to his post-presidential years, he was invited

to partner with a number of institutions, including several

universities and the University System of Georgia.

“I

met with Dr. Laney, and I finally decided that I would rather

go to a private institution,” Carter told Emory Magazine.

“I wanted the unrestricted ability to speak to the students

in a very frank and unrestrained way on controversial issues

of the times, and I felt Emory would give me that opportunity.

Since I have been a professor at Emory, I have always been able,

in class and lecture halls and town meetings, to speak without

restraint.”

Carter

also was drawn to Emory because the institution had world-class

ambition, yet was firmly planted in the soil of his homeland,

in the fertile region whose culture, religion, politics, social

structure, and agriculture shaped his identity from boyhood.

“I

was always heavily affected in my attitude toward politics by

the realization that I was the first president from the South

since James K. Polk,” Carter says. “It was a wonderful

blessing for me, but also something of an obligation not to

betray that confidence, to represent the region positively and

accurately. . . . I think the basic philosophy of Emory, the

basic character, I consider to be Southern, while at the same

time competing very well on a national and international basis

in research and quality.”

The

same year Carter became University Distinguished Professor,

he created the Carter Center in partnership with Emory. At Laney’s

suggestion, an office on the tenth floor of the Woodruff Library

became the center’s first home, and its presence brought

an air of excitement and prestige to the campus.

“I

knew that the center would be unique, because it was to be a

partnership between a former U.S. president with enormous energy

and a university on the rise, and nothing like that had ever

been tried before,” says Steve Hochman, now director of

research for the center, who was one of the first three staff

members assisting Carter in the library office. “However,

no one imagined exactly how the Carter Center would develop.”

From

the beginning, Carter’s vision for the center was focused

on action. He also stipulated that the center would not duplicate

the efforts of others but direct its resources toward needs

not already being met.

“President

Carter wanted Emory faculty to participate in action-oriented

programs,” says Kenneth W. Stein, William Schatten Professor

of Middle Eastern and Israeli Studies and the center’s

Middle East fellow since 1986. “He was not interested in

programs where we’d have a conference, write a book, and

it would end up on a library shelf.”

By

partnering with Emory, Carter had secured for the center a stable

of experts in almost all imaginable aspects of world politics

and health care, many of them scholars who were eager to venture

out of the classroom to the farthest-flung African villages

or the enclaves of Middle East governance to wield their knowledge

for practical good. Like Stein, the earliest Carter Center fellows

were Emory faculty members who served joint appointments, their

dual roles informing and enriching one another. The growing

relationship between the institutions was both organic and symbiotic.

“As

the Carter Center evolved from the original concept of just

conflict resolution to a wider range of programs involving health

care and agriculture and democratization,” Carter says,

“we saw the advantages of bringing in experts on these

particular subjects, and it was a natural development to have

them be jointly employed by the Carter Center and Emory. It’s

been very advantageous for us over the years. There were times

when almost all our fellows were Emory professors, but nowadays

the Carter Center work is so extensive and challenging that

the fellows have to concentrate mainly on their work at the

center.”

In

1982, Stein was recruited to serve on a committee that helped

outline the mission and structure of the Carter Center. At a

planning retreat on the Georgia coast that included an array

of top advisers from the Carter administration, Stein had a

rare opportunity to sit by the ocean with the former president

and discuss the Middle East and the Camp David Accords for several

hours. It was an extraordinary, life-changing experience for

Stein, a conversation which would later be the springboard for

his book Heroic Diplomacy. On the plane home, Stein says, Emory

President Jim Laney, who holds a degree in theology, commented

on Stein’s intense talk with Carter. Stein says he asked

Laney, “Can you imagine what it would have been like for

you to have interviewed Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John?”

Laney raised an eyebrow and said, “It was that good?”

And Stein replied without hesitation: “It was that good.”

Stein

was one of many in the Emory community caught up by Carter’s

ambition, influence, and can-do optimism. “There was a

lot of energy and excitement in the air,” says Sam Nunn

Professor of Law Harold J. Berman, who was named Carter Center

fellow of Russian law in 1985. “We had fellows’ meetings

where we discussed not only the future of the Carter Center,

but the future of humankind. Jimmy Carter was terrific in those

sessions. He ran those meetings with great dignity, imagination,

and intelligence.”

Until

the Carter Center facility opened in 1986, its major conferences,

or consultations, as Carter dubbed them, were hosted at Emory.

The first, in 1983, was a consultation among international leaders

on the Middle East, directed by Stein, with former President

Gerald Ford joining Carter as co-chair. It quickly became apparent

how powerful the Carter Center could be, with a former president

leading the charge; it also became clear that Emory would benefit

as well.

“When

we found ourselves associated with President Carter,” Stein

says, “we were suddenly in an environment where he could

call upon virtually any person in the world and ask them for

advice, or ask anyone to confer with him at the Carter Center.

After trips [to the Middle East] with the Carters, I could come

back to my classes and say, ‘Three weeks ago I said this,

and then last night, in a private conversation between Carter

and the president of Jordan, this happened.’ There was

not a single year when my exposure [to the center] did not make

a difference in what I could bring to my students.”

In

1986, the Carter Center, housed alongside the Carter Presidential

Library in a cluster of contemporary buildings and gardens located

between Emory and downtown Atlanta, was dedicated with a gathering

of dignitaries including President Ronald Reagan. In the ensuing

years, as the center’s resources, staff, funding, and international

reputation have risen and its peace and health programs both

expanded and become more clearly defined, Carter has continued

to look to Emory fellows to shape its mission and guide its

work; the connection between the institutions is evolving still. In

1986, the Carter Center, housed alongside the Carter Presidential

Library in a cluster of contemporary buildings and gardens located

between Emory and downtown Atlanta, was dedicated with a gathering

of dignitaries including President Ronald Reagan. In the ensuing

years, as the center’s resources, staff, funding, and international

reputation have risen and its peace and health programs both

expanded and become more clearly defined, Carter has continued

to look to Emory fellows to shape its mission and guide its

work; the connection between the institutions is evolving still.

Richard

Joseph, Asa Griggs Candler professor of political science, joined

the Carter Center in 1988 as fellow for African studies to lead

much of the center’s extensive efforts in Africa. Robert

Pastor, formerly President Carter’s national security adviser

for Latin America, became a fellow for Latin American affairs

and Emory professor of political science.

Ellen

Mickiewicz, then dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences,

also served as a fellow for the Commission on Radio and Television.

She and Carter sponsored a program to help encourage free press

in the Soviet Union in which they monitored Soviet telecasts

through antennas atop two Emory buildings.

And

William Foege, University Presidential Distinguished Professor

of International Health, served as executive director of the

Carter Center from 1986 until 1992. Foege, whom Carter describes

as “one of my personal heroes,” previously had been

director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and

was the first director of the Carter Center’s international

health programs. More than any other, Foege’s vision and

expertise shaped the Carter Center’s global health programs,

guiding them to identify the greatest needs and meet them most

effectively.

Currently,

Joyce Murray, professor of adult and elder health at the Nell

Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, spends forty percent of

her time working for the Carter Center and sixty percent for

Emory. Murray recently was named director of the Center’s

Ethiopia Public Health Training Initiative, an interdisciplinary

teacher education program designed to give health professionals

the tools needed to address care shortages.

Frank

Richards, associate clinical professor of pediatric infectious

disease at the medical school and an adjunct faculty member

in the school of public health, spends most of his time directing

the Carter Center’s river blindness programs. Although

he doesn’t teach full time, he depends on Emory students

to help with his research and analysis. They, in turn, learn

how their public health education can be put to work.

In

particular, the ties between the Carter Center and the Rollins

School of Public Health are growing stronger. Rosalynn Carter,

long an advocate for better treatment and prevention of mental

illness, has worked with Emory’s public health programs

to incorporate mental health into the curricula. In 1998, she

established the Rosalynn Carter Endowed Chair in Mental Health.

“[One]

of the main things that the Carter Center has tried to initiate

has been the formation and expansion of the school of public

health to deal with issues that we address,” Carter says.

From

three people in an

office at the top of Emory’s Woodruff Library, Carter has

grown his idea into an internationally known and respected organization

with a staff of 150, an annual budget of $35 million, and active

programs all over the world. After twenty years, the center’s

momentum is unstoppable.

“The

Carter Center has built a reputation of integrity, of benevolence

and care,” Carter says. “My personal role and that

of Rosalynn is dropping off precipitously.”

Even

as Carter continues to craft his legacy, it is clear that its

impact can never be fully measured. But at least part of his

achievement lies in those Emory scholars and students whom he

has taught, inspired, and beckoned to service.

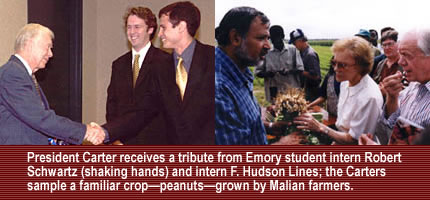

Student

interns, who formed one of the earliest ties between Emory and

the Carter Center, remain one of the strongest. The center recruits

ten to twelve upperclassmen each semester, says Pete Mather,

director of educational programs, and directors rely on them

to keep tabs on political situations around the world and conduct

research critical to the center’s mission.

For

University senior and Woodruff scholar Robert Schwartz, his

internship altered the course of his studies and his future.

Schwartz became interested in the Carter Center after getting

an autograph from the former president during his freshman year.

Now he plans to write his thesis on free trade in the Americas,

based on knowledge he gained at the Carter Center.

“Everything

I have learned at Emory, I am now applying at the Carter Center,”

said Schwartz, in a recent speech to the Emory Board of Trustees.

“I write biweekly updates for President Carter on Cuba,

and I am in the process of preparing a report on the electoral

situation in Argentina for Dr. [Shelley] McConnell. In turn,

the Carter Center has given me amazing opportunities. I have

been able to attend the U.S.-Chile Free Trade Negotiations,

and . . . I gave input on President Carter’s ‘Open

Letter of Invitation to the Americas,’ which [Atlanta]

Mayor [Shirley] Franklin read in Quito. Dr. McConnell actually

listened to my advice, and I was so proud to see the results

of our conversation not only in the Associated Press, but also

on the front page of the Emory Wheel.

“I

truly have made a difference, at Emory, at the Carter Center,

and in the world.”

|

|