Associate

editor Mary J. Loftus visited five Emory alumni in

the City of Light last summer. Her interview with

Michael Golden ’84MBA, publisher of the

International Herald Tribune, anchors our special

section, Emory in Paris. The following links will

bring you to stories about fellow alumni Syed

Hoda ’96MBA, Marilyn

Kaye ’71C-’74G, Marcio

Mendes ’98B, and Ronnie

Rubin ’76C.

Golden

Opportunity

A

scion of the New York Times family wants

to make the International Herald Tribune

required reading worldwide

Just

outside the Paris headquarters of the International

Herald Tribune, at 6 bis rue des Graviers, the

day’s paper is displayed behind glass so passersby

can read the top news stories.

On

this humid morning in late July, the Herald Tribune’s

front page is a reader-friendly mix of politics,

business news, and current events. Headlines read:

“In Europe, passionate cheering for Kerry”;

“Google is bullish on its own worth”;

“Russians take aim at imitators of the AK-47.”

Datelines pepper the pages from London, Mexico City,

Cairo, Berlin, and Moscow.

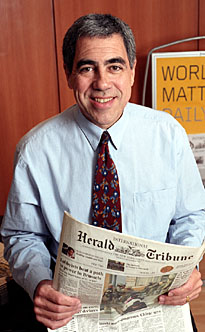

Inside,

publisher Michael Golden

’84MBA (left) strides through the

first-floor newsroom, where editors and reporters

are busily transcribing notes and reading wire copy.

A vice president of The New York Times Company and

a member of the family that controls the newspaper,

Golden was named publisher of the International

Herald Tribune in November 2003 and was charged

with revitalizing the century-old paper, which bills

itself as “The World’s Daily Newspaper.”

Though distributed in 185 countries, it had been

losing money for several years. Inside,

publisher Michael Golden

’84MBA (left) strides through the

first-floor newsroom, where editors and reporters

are busily transcribing notes and reading wire copy.

A vice president of The New York Times Company and

a member of the family that controls the newspaper,

Golden was named publisher of the International

Herald Tribune in November 2003 and was charged

with revitalizing the century-old paper, which bills

itself as “The World’s Daily Newspaper.”

Though distributed in 185 countries, it had been

losing money for several years.

“A

paper has to be a financial success in order to

survive,” says Golden. “There’s no

such thing as a successful, nonprofitable newspaper.”

Golden,

fifty-five, has worked in management positions at

The New York Times Company for the past twenty years,

largely in the company’s magazine group, serving

as production manager of Family Circle and

publisher of McCall’s and Tennis magazines.

He became vice chairman and senior vice president

of The New York Times Company in 1997.

Upon

being named publisher of the International Herald

Tribune, Golden and his wife, Anne, moved from

New York City into a furnished Left Bank apartment

in the Sixth Arrondissement. He has spent the months

since working to make the International Herald

Tribune required reading around the globe.

Although

the Herald Tribune is competing with the

likes of the Financial Times and the Wall

Street Journal, Golden doesn’t intend it

to become strictly a business publication. Indeed,

the Herald Tribune offers plenty of lighter,

brighter fare: this day’s style section is

anchored by an article on “demure swimsuits”

coming back into fashion, accompanied by photos

of high-fashion models in retro tanks, and the culture

pages mix movie and book reviews with tidbits of

Hollywood gossip. Even the grey listings of stock

quotes from the New York Stock Exchange, NASDAQ,

and other world markets are capped off by a half-dozen

American comic strips, from “Dilbert”

to “Doonesbury.”

“We

want to be a ‘must-read’ as well as a

‘want-to-read’ paper in the office and

at home,” Golden says. “We’re of

interest to people who want to gain the broader

business perspective, which includes politics, economics,

cultural trends, and fashion.”

Golden,

who has a master’s degree in journalism from

the University of Missouri and an MBA degree from

Emory, has the demeanor of a confident newsman who

is comfortable with all sides of the business. As

well he should: he was born into a family with newspaper

ink coursing through its veins. His great-grandfather,

Adolph S. Ochs, the son of poor German-Jewish immigrants,

bought the Chattanooga Times in 1878 and

the New York Times eighteen years later.

Golden’s grandfather, Arthur Hays Sulzberger

(Ochs’ son-in-law), was the publisher of the

New York Times from 1935 to 1961. His mother,

Ruth Sulzberger Golden Holmberg, was the publisher

and chair of the Chattanooga Times for almost

thirty years.

The

sense of the Times as a family enterprise persists:

fourth-generation descendants, Golden among them,

own a large portion of New York Times Company stock,

control the board of directors, and set policies

on everything from making charitable donations to

involving the next generation.

“The

company has been a real point of cohesion for us,”

says Golden. “We realize the reason the family

is still together into the sixth generation, who

are really just babies at this point, is because

of the business.”

Shortly

after Ochs bought the New York Times in 1896,

he established the paper’s slogan, “All

The News That’s Fit To Print,” as a jibe

to competing papers known for yellow journalism.

The paper had gained such popularity by 1904 that

when it relocated to a new office on Forty-second

Street, the area was named Times Square. A century

later, The New York Times Company is a publicly

traded multimedia conglomerate with annual revenues

of $3.2 billion. Among its marquee holdings are

the New York Times, the International

Herald Tribune, and the Boston Globe,

as well as sixteen other newspapers, eight network-affiliated

television stations, two New York City radio stations,

and more than forty Web sites, including NYTimes.com

and IHT.com.

Until

recently, the International Herald Tribune

had been owned in a 50-50 partnership by the New

York Times and the Washington Post–two

competitive family dynasties sharing an unlikely

joint venture. In 2002, according to an article

in the Post’s financial section, the

Times Company “forcefully maneuvered”

the Washington Post Company into selling its half

of the paper for $65 million, “leaving Post

company executives bitter.”

“It

was more contentious than a business deal,”

Golden admits. “You could characterize it as

a divorce. But we were absolutely convinced that

dual ownership wasn’t working. Instead of two

owners, there was no owner.”

In

the seven years since Golden’s first cousin,

Arthur Sulzberger Jr., took over as publisher of

the New York Times from his father, the company

has aggressively expanded the New York Times

brand across various media, from the Internet to

television stations. The purchase of the International

Herald Tribune and the placement of Golden at

the helm were intended to expand the company’s

influence across continents.

“The

New York Times had become a national newspaper,”

Golden says, “so we started turning our attention

toward a global-international newspaper.”

“Michael

has a deep and rich understanding of the newspaper

industry in general and The New York Times Company

in particular,” Sulzberger said when announcing

the appointment in 2003. “I am confident [he

and his team] will bring the paper’s quality

journalism to an even larger global audience.”

Golden,

for his part, was eager to take up the challenge.

He speaks French, having spent a few years teaching

English at the Franco-American Institute in Rennes,

where he lived with Anne after receiving his bachelor’s

and master’s in education from Lehigh University

in 1974.

“When

Michael first told me of his new job opportunity,

it was, obviously, a complete surprise. And a bit

of a shock. We were leading a very comfortable life

in New York,” says Anne Golden, who met Golden

in college and married him in 1971. “But my

very first reaction to the question, ‘How would

you like to live in Paris?’ was basically an

immediate and unqualified ‘yes.’ ”

They

talked at length about the pros and cons over dinner

that night, but with both their daughters grown–twenty-eight-year-old

Margot is a student at Arizona State University

in Tempe, and twenty-five-year-old Rachel is a marketing

coordinator at the Denver Newspaper Agency–there

was little hesitation.

“We

knew,” says Anne Golden, “that this would

be a fascinating adventure.”

She

firmly believes her husband is the right man for

the job. “Michael is a very good listener and

he likes looking at the big picture. He is really

good at synthesizing other people’s opinions

and making sense of long conversations or meetings.

He understands the need for compromise and is quite

good at recognizing people’s strengths.”

Golden,

who, like many executives, relies on knowing when

to delegate and to whom, says many of the skills

he learned in Emory’s executive MBA program

have proven essential.

“Having

that base of knowledge was useful because it broadened

my field of vision and allowed me to engage with

the business side of the newspaper,” he says.

“I can follow pretty complicated accounting

conversations. And I’m able to [detect] whether

other people are blowing smoke or not.”

Golden,

who served on the board of directors of the International

Herald Tribune for five years and was familiar

with its operation, has skillfully guided the paper

through this difficult transition, says Alison Smale,

deputy foreign editor of the New York Times,

who came to the Herald Tribune to serve as

its managing editor in January 2004.

“Under

Times-Post ownership, there had been no court of

adjudication between what the business side and

the journalism side felt was right for the paper,

and they were left to tussle it out,” Smale

says. “The paper lacked a single, unified vision.

Michael’s a very balanced individual, quite

secure in his own skin. He used classic management

techniques to inculcate a firm sense of mission

across the board.”

That

mission, says Golden, is one shared by the entire

New York Times Company: to enhance society by creating,

collecting, and distributing high quality news,

information, and entertainment.

“We

have to be lively and engaging as well as informative

and thought provoking,” he says. “The

scarce resource today is time. Whether it’s

watching CNN, reading Newsweek, or taking the kids

to school, people have a lot to do. If your product

is not high enough on their list of priorities,

it’s not going to make it.”

His

values, says Golden, are still based on those held

by his great-grandfather long ago.

“We

follow a lot of the same principles that Adolph

Ochs articulated,” he says. “The New

York Times was a failing paper when he bought

it. But he reduced the sale price from three cents

to two cents while increasing the quality. He believed

strongly in the separation of news and advertising–that

one didn’t influence the other. And he recognized

that the only thing we have to sell is the credibility

and reputation of the paper.”

One

of the internal debates at the International

Herald Tribune has long been, “Is the paper

too American?” In fact, the intent at first

was to rename the International Herald Tribune–which

began as the Paris edition of the New York Herald

Tribune in 1887– the International

New York Times. But market research showed

widespread resistance to the reflagging.

“The

report back was clear,” says Golden, drinking

coffee in the rooftop conference room where such

decisions are often hashed out. “The International

Herald Tribune was seen as an independent international

newspaper, and the International New York Times

was seen as American. The decision was easy.”

Since

many of the Herald Tribune’s stories

are supplied by the New York Times’

fifteen hundred reporters, the paper can hardly

avoid an American flavor, but Golden is instituting

changes both large and small to make the paper more

global–such as increasing coverage of world

markets; including more soccer, cricket, and rugby;

and adding a variety of voices to the op-ed pages.

He’s also overseeing general editorial improvements,

such as extending deadlines to accommodate more

breaking news, expanding the amount of news space,

and adding color to the front and back pages.

The

Herald Tribune strongly courts elite international

executives and opinion leaders, as well as readers

who consider themselves “global citizens.”

The biggest markets for the Herald Tribune,

which has a daily circulation of about 245,000,

are France, Japan, Germany, South Korea, and Switzerland.

“The

audience of the International Herald Tribune

is fundamentally different than the audience of

the New York Times,” Golden says. “They

are both affluent, well-placed in their careers,

and interested in a wide range of information. But

the International Herald Tribune’s readership

is one-third American expats and Americans traveling

abroad, one-third expats from other countries, and

one-third [French] nationals.”

“The

IHT may have an American style of journalism, but

it is an international publication. We create our

own face and our own scoops,” Smale says. “We

just did a series on the European Union that we’re

very proud of, and we have taken the lead on talking

about what constitutes the new Europe and the limits

of European unity. It’s amazing to me that

from the western shores of Ireland to the borders

of the Ukraine, people voted to send representatives

to the same democratic legislature.”

At

the same time, she says, “Europeans and others

are thirsty for news about the United States and

its participation in the world at the moment. I

can’t imagine that will abate. And, through

our ever-closer attachment to the New York Times,

we have access to the best Washington reporting

there is.”

Publishing

an English-language newspaper owned by an American

company for a world readership is often an exercise

in diplomacy. But Golden harbors no doubts.

“The

International Herald Tribune is one of the

world’s great newspapers,” Golden says.

“The breadth of its news report is unique among

daily global papers and it is valued for its strong

and independent voice. We are building upon an already

strong base.”

|