Magical Thinking

A landmark conference on contemplative studies highlights Emory faculty's progress and potential in this emerging field

iStockphoto

What if there were a treatment for every negative emotion and destructive behavior imaginable, from depression and anxiety to anger and violence, even to something as simple as poor eating habits? What if this same treatment could also help people learn more effectively, see things more clearly, access their true potential, and understand their relationship to other beings? And what if the treatment were free, available without a prescription, and potentially accessible to everyone?

In the growing field of contemplative studies, scholars are exploring whether the practice known as mindfulness may be such a treatment. Several Emory experts who have studied this innate human faculty are working together and with others around the world to both scientifically prove its effectiveness and increase its acceptance in clinical settings and classrooms.

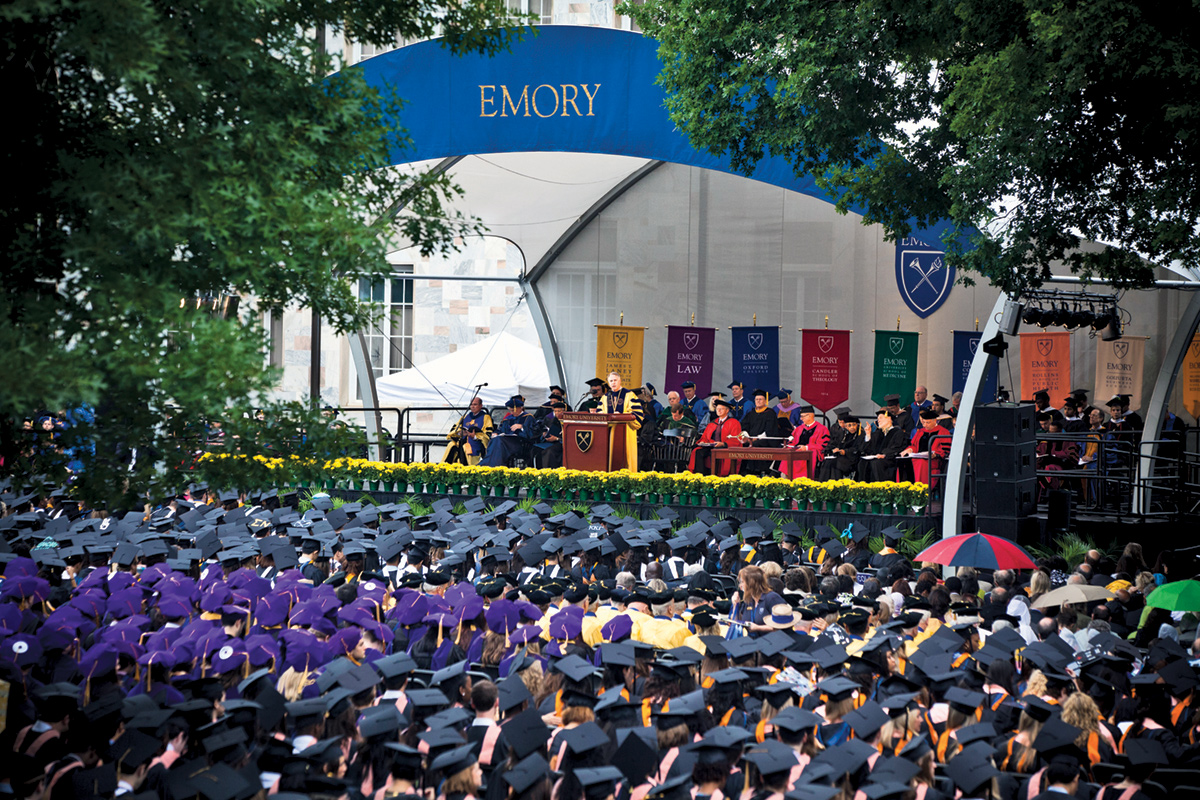

They recently gathered in Denver at the inaugural International Symposia for Contemplative Studies to showcase their findings to each other and more than seven hundred others who attended. Sponsored in part by the Emory Collaborative for Contemplative Studies (ECCS), the event was historic, bringing together original sages in the field—including MIT molecular biologist Jon Kabat-Zinn, who originated mindfulness-based stress reduction in the 1970s—and newer stars, including Emory’s John Dunne, a Buddhist scholar who is working to define the generic term meditation.

The event created a venue for researchers in basic and applied science, academia, and contemplative traditions to figure out how to integrate “first-person data,” or information that is gleaned from sensual, conscious experience, with “third-person data,” which is gathered by measuring brain processes and physical and behavioral responses using scientific instruments.

Credibly bridging this gap—between what contemplative practitioners have experienced and described for more than two millennia and what Western science can precisely measure—was the pervasive theme of the event.

Mindful definition

Dunne, associate professor of religion, says it’s essential to define meditation—the primary tool used to become mindful—for the sake of the field’s integrity.

“What is meditation? Is it a particular way of sitting, a particular way of thinking? Is it a single thing?” he asked the audience during his master lecture. “One of the issues is that no one specifies what meditation is, so it becomes a kind of magical black box: you put an unhappy child in the box and she comes out a happy child.”

So what happens when a fundamental term is undefined? “It’s easier to ignore inconsistencies in meditative practices, personal bias in research, the potential for negative side effects, and doubt when there isn’t one agreed-upon definition,” he said, noting that transcendental meditation suffered credibility issues in the late 1980s in part because it was a copyrighted process that scientists could not examine.

Dunne and a team of researchers are getting inside that magical black box—working to develop a multidimensional, phenomenological model that examines the facets of meditation that cut across various styles of practice, maps them in conceptual space, and begins to understand how they work.

“By being specific and getting into the nature of the mechanisms of meditation, we can generate a hypothesis, operationalize the practices, and develop theoretical accounts that can then be tested,” he says.

One such mechanism in Dunne’s model, found in ancient Buddhist texts and used in current practices, is reification—the perception of things as being real even though they aren’t. Dunne illustrated it by describing to the audience red, ripe strawberries that were organic and sweet, with chocolate sauce on top, and then showing a picture of the fruit. People’s mouths began to water simply at the description and image; the actual fruit wasn’t required to elicit this response, this false perception of reality.

Dunne says reification is potentially the most important aspect of mindfulness because people have the natural, built-in capacity to de-reify—to recognize that their thoughts aren’t real.

“Thought loses its power when you realize it’s just a thought,” he says. “You just have to get out of the way to let it happen. Simple instructions in this practice should allow this to come online very easily.”

Mindful eating

Lawrence Barsalou, Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Psychology at Emory, is proving such effects in the lab. Working with lead investigator Esther K. Papies of Utrecht University, he has used reification as a means of changing people’s behavior toward food.

Subjects received a twelve-minute training session in mindfulness meditation that helped them understand that their reactions to external stimuli were transient thoughts rather than real experiences. In the first test, they were asked to recognize their reactions when viewing images of highly attractive food, such as chocolate cake, and neutral food, such as celery. In the second phase, they were shown additional food images and told they could press a button to make any of the images come closer or move further away. The control group did not receive the mindfulness training.

The outcome? The subjects with mindfulness training were consistently less reactive to the food images than the control group—they were slower to push the button to enlarge the attractive food, a finding that could be used to help people maintain more healthful diets.

“The results are quite surprising—that just twelve minutes of mindfulness training reduced the desire to react to attractive food,” says Barsalou.

Mindful caregiving

Susan Bauer-Wu, associate professor of nursing at Emory, discussed her work to bring contemplative practices to professional caregivers, such as nurses and doctors.

“Clinicians are highly stressed. What is missing is how they can be present in their work,” said Bauer-Wu, author of Leaves Falling Gently (New Harbinger Publications, 2011) for seriously ill and dying patients.

Bauer-Wu teaches in an eight-day training program that “marries practices of the Dharma with science” to help clinicians reconnect with themselves so they can better connect with their patients. Students sit on cushions and learn mindfulness and compassion meditation. But because clinicians are typically trained to be skeptics who need hard evidence, Bauer-Wu says it’s essential that they understand the growing scientific evidence behind meditation—what it means to stabilize the mind, and the importance of neuroplasticity, or the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. She also outlines how connection with one’s own body and emotions is essential to being able to show empathy.

“They attend the training because something is missing in their professional lives and they are yearning for something deeper. They are on the brink of drowning in the system,” Bauer-Wu says. “When they are open to mindfulness practice, they recognize that the changes within themselves also will be transformative for their work with patients and families.”

Mindful living

Emory faculty provided a number of other presentations at the landmark conference. For example, a team of researchers led by Geshe Lobsang Tenzin Negi, senior lecturer and director of the Emory-Tibet Science Initiative, explained cognitive-based compassion training (CBCT), a meditation training protocol his team developed and has been using to change the behavior of young school children and foster children. Teresa Sivilli, a researcher in the School of Medicine, showed how CBCT helps people more accurately read the emotions of others, while Thaddeus Pace, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, outlined how CBCT helps people improve their interactions with others.

Faculty also led a panel discussion about how they’ve built the Emory Collaborative for Contemplative Studies, a network that has bridged the sciences and humanities since 2005, mostly without funding.

“This has grown beyond an interdisciplinary approach to education,” says Bobbi Patterson, professor of pedagogy in religion. “It’s allowing the constellations to emerge in the form of new courses, ideas, and personal histories.”