|

|

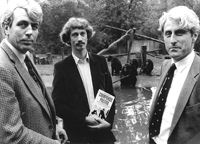

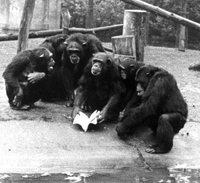

In the late 1970s, I began writing Chimpanzee Politics, a popular account of the power struggles among the Arnhem males. The chimps had conveniently waited to challenge the existing order until about one year into my study, when I had acquired a good grasp of their personalities and behavior. At thirty-two years old, I was risking my career ascribing Machiavellian tactics to animals. I had been trained to avoid any talk of intentions or emotions in my subjects. Animals were to be described as soul-less machines. Obviously, no one follows this rule with regards to human behavior, and I questioned the wisdom of different standards for species with so much shared evolutionary history. If two closely related species show similar behavior, it is far more parsimonious to come up with one explanation for both. Desmond Morris greatly facilitated the publication of Chimpanzee Politics, translated into English from my Dutch original. It first appeared in London, in 1982. The Dutch edition was presented the same year at the Arnhem Zoo, where I stood in front of the ape island flanked by the van Hooff brothers. A copy of the book was thrown across the moat to its leading characters, who acted as if they were going to read it. The book was a great success, and remains on the market today. Some of my colleagues may have grumbled, but many others welcomed Chimpanzee Politics. It introduced the term "Machiavellian" to the vocabulary of primatologists. In retrospect, it is clear that the time for this was ripe. Donald Griffin had just published Animal Awareness. Cognitive psychology was on the rise, and cognitive ethology was sure to follow. The U.S. Speaker of the House, Newt Gingrich, put the Arnhem political saga on the recommended reading list for freshmen Congressmen, in 1994. But the German edition came out under the condescending title Unsere Haarigen Vettern ("Our Hairy Nephews"), while the French publisher decided to make fun of Mitterrand and Chirac by putting them on the cover with a chimp between them. Both publishers held out for the opposite of what I tried to achieve: to instill respect for the apes. Nowadays, book contracts give me veto rights over cover image and title translation. Thanks to Catherine, I knew French attitudes well since I spent considerable time in France, where Charles Darwin still lingers in the shadow of René Descartes. Photo 13 shows me with a Spanish friend, Alejandro Arribas, in Paris. We spent hours debating the cultural side of human biology, reflected in Alejandro's later books on the topic (photo 14) and my own The Ape and the Sushi Master (2001). |

|||||||||

| NEXT>> | ||||||||||