Expert in Complexity

Carrie Wickham examines the evolution of the Muslim Brotherhood

Mahmoud Khaled/AFP/Getty Images

Carrie Wickham

Ann Borden

It is difficult to imagine a subject more timely, volatile, and elusive than that of Carrie Rosefsky Wickham’s The Muslim Brotherhood: Evolution of an Islamist Movement. Since its publication last summer, events in Egypt have continued to move with astonishing rapidity, and Wickham is increasingly sought out as a guide to the complexity of Egyptian politics. As Lisa Blaydes reports in a recent Boston Review article about Wickham’s book, she walked into the office of Essam el-Erian—deputy leader of the Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party—in 2007 for an interview. His first question to her was, “Do you know Carrie Wickham?”

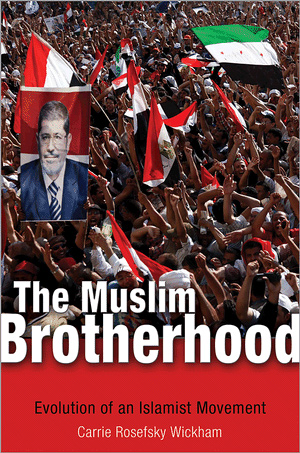

The cover of the book depicts Muslim Brotherhood supporters celebrating the ascendancy of Brotherhood leader Mohamed Morsi to the presidency on June 24, 2012. Just one year later, on July 3, 2013—the same month Wickham’s book was published—he was removed from office and charged with, according to the New York Times on September 1, “inciting his supporters and aides to commit the crimes of premeditated murder” as a result of December 2012 clashes that resulted in widespread deaths. El-Erian remained free longer, but was himself arrested on October 30.

Wickham, associate professor of political science, hardly had time to bask in the successful launch of her second book: a scant six days after its release, she weighed in with the op-ed “Egypt’s Missed Opportunity” in the New York Times; more recently, in the Guardian, she wrote a piece warning that a ban of the Brotherhood will worsen Egypt’s divisions.

Wickham has been covering the Muslim Brotherhood since her dissertation fieldwork began in 1990. In 2002 she authored Mobilizing Islam: Religion, Activism, and Political Change in Egypt. The research for her current book began in 2004 and involved 124 interviews—including one with Morsi before his presidential run—with Islamist and secular civic and political activists, academics, and journalists in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Kuwait.

It is remarkable testimony to Wickham that an American woman could gain the trust of this group of men. Most of those interviewed spoke in Arabic to her, and all translations in the book—except where noted—are her own. The book also draws on Arabic-language primary-source documents, books, research reports, and media articles that other Western researchers have failed to mine.

The Muslim Brotherhood, despite its thrust into the political limelight with Morsi’s presidency, has seemed to thrive on the sidelines and in the shadows for much of its history. Founded by Hasan al-Banna in 1928, the Brotherhood—according to Wickham—“is the flagship organization of Sunni revivalist Islam and has been in existence longer than any other contemporary Islamist group in the Arab world.” It had its beginnings as a small religious and charitable society. As Wickham reveals, the group’s goal was not to seize power for itself, but to serve as a catalyst for “a broad process of social reform that would lead eventually and inevitably to the establishment of an Islamic state.”

More than eighty years after the Brotherhood’s founding, the wait continues. Wickham captures the paradoxical condition of the Brotherhood on the day of Morsi’s election, June 30, 2012: “An Islamist organization that had spent most of its existence denied legal status and subject to depredations of a hostile authoritarian state was now in charge of the very apparatus once used to repress it. And it had reached those heights not by way of coup or revolution but through the ballot box.” Despite a string of electoral victories, the Brotherhood’s power was never secure—nor was their constitution backed by a wider national consensus.

Both in the book and in more recent comments, Wickham stresses the need for what she calls a “healthy dose of humility” with regard to the Brotherhood. There is still much we don’t know about its operation. And its contradictions are many, starting with the fact that women play an active role but are denied formal rights and have little say. Reformists contend with conservatives in a perpetual seesaw for the balance of power that can result in expulsion for internal critics of the group’s senior leadership. Calling Wickham’s work “an excellent new history,” Paul Danahar of the Guardian notes that “her research in both Arabic and English has revealed several brotherhoods, oscillating between secrecy and transparency, modernity and the example of the Prophet Muhammad.”

What lies ahead for the Brotherhood? Many will look to an American woman and Emory faculty member for thoughtful, nuanced answers.