Immunology Research May Lead to Long-Sought TB Vaccine

Latent infections may be key to future prevention

Jack Kearse

Emory scientists are looking for ways to control an ancient disease by solving one of its key mysteries: Why is it that most people with a latent tuberculosis (TB) infection never develop TB symptoms, but others do?

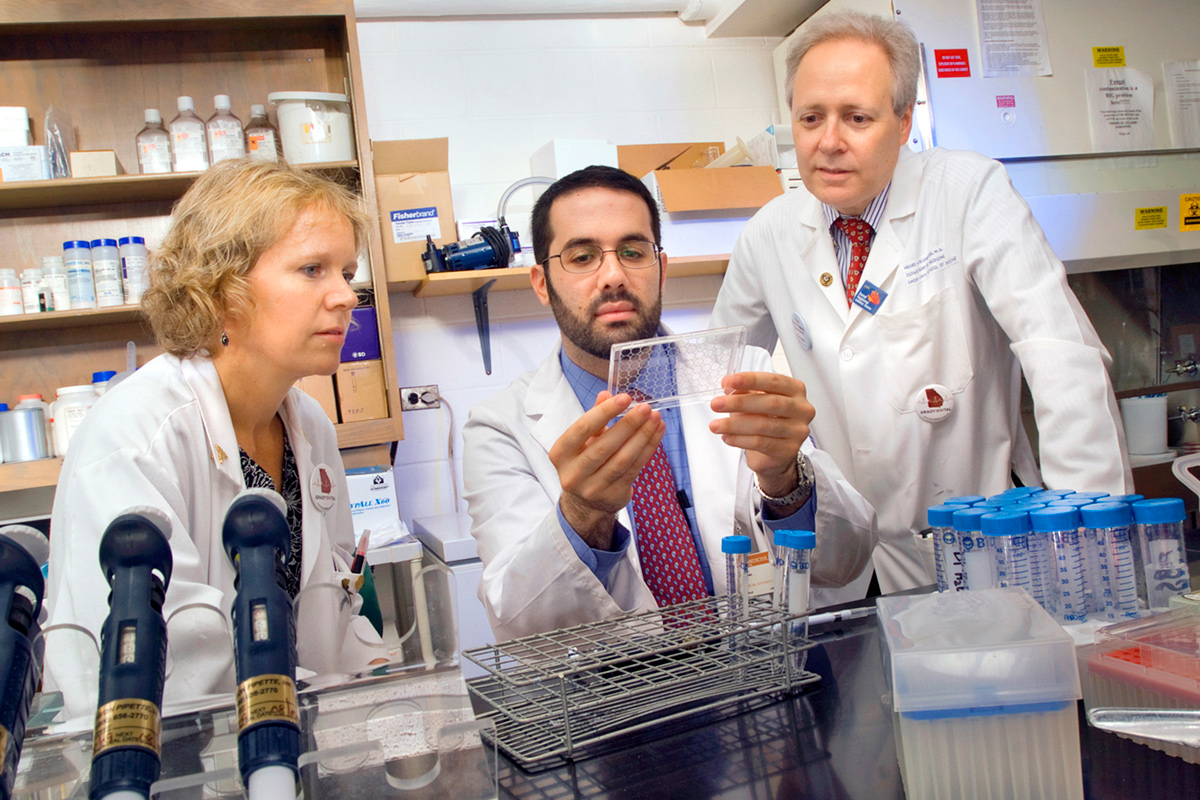

The answer is likely to be found in studying and comparing the immunology of the two affected groups, according to Henry Blumberg, professor of medicine in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the School of Medicine and professor of epidemiology and global health in the Rollins School of Public Health.

Blumberg is principal investigator for an Emory-led Tuberculosis Research Unit (TBRU), one of four such collaborations recently established by an $18 million, seven-year grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Coprincipal investigator is Joel Ernst of New York University, one of seven Emory TBRU partner organizations.

“When people say ‘tuberculosis’ they usually mean active TB disease,” Blumberg says. “These people are generally very sick, and they have symptoms that may include cough, fever, weight loss, and night sweats. If they have pulmonary TB or the disease is in their lungs, they can spread it to other people through the air.

“But there’s another state called ‘latent TB infection’ where someone has been exposed to someone with active TB disease and they became infected, but they don’t have symptoms and they can’t transmit the disease while asymptomatic. In most cases, their immune system keeps the bacteria in check for the rest of their lives, but in some cases, the onset of symptoms is only delayed temporarily, anywhere from weeks to years after the initial exposure and infection.”

According to numbers from the World Health Organization, an estimated two billion people—one-third of the world’s population—have latent TB infection, of which between 5 and 10 percent will develop active TB. About nine million people became ill with active TB in 2013, and 1.5 million died from the disease. More than five hundred thousand children developed TB that year, and eighty thousand died from the infection.

People with latent TB infection can progress to full blown TB when their immune systems are weakened. The risk of developing TB is up to twenty times greater in people living with HIV, and one in four AIDS-related deaths is due to TB.

“We’re trying to learn more about the spectrum between asymptomatic, latent TB infection and active TB, especially as it concerns T-cell immunology and the factors associated with controlling infection,” Blumberg explains.

“To control TB throughout the world, we need an effective TB vaccine, and we don’t have one right now. So, we’re hoping that some of our findings could help the people who are trying to develop one.”

The research effort is divided into three projects. In project one, researchers are searching for a better way of measuring whether or not someone carries the TB bacteria. Existing tests—notably the TB skin test—will produce a positive result if a latent TB infection is present. But it also comes back positive if the bacteria had been present at some earlier point but have since been cleared by the immune system.

Instead, scientists hope to identify certain characteristics or signatures in T-cell response that would accurately indicate whether or not there are TB bacteria inside a person’s body.

“If you can identify the people who are actually at risk,” explains project coprincipal Cheryl Day, assistant professor in the Department of Global Health at the Rollins School of Public Health, “then you’ll be able to target treatment more efficiently and effectively.”

Both projects one and two involve a set of cohort studies in which researchers monitor the health of TB-infected people over a period of time at two sites: one in the US and the other in Kenya. Blood samples are obtained at regular intervals and detailed immunological studies are performed. In project two, since some of the participants in Kenya will likely develop active TB, the expectation is that study data will reveal characteristics of the immune response that signal long-term control of TB infection as well as immune-system changes that occur when a latent infection becomes an active one.

The third project, a collaboration between Yerkes National Primate Research Center and the Tulane National Primate Research Center in Louisiana, uses a nonhuman primate model to determine the profile of immune responses that correspond with latent TB infection versus treated infections versus reactivation of the TB bacteria, says Francois Villinger, codirector of project three and chief of the Yerkes Division

of Pathology.

“We have some understanding of what can make a latent TB infection become active,” says Villinger, referring to pathogens such as HIV that compromise the immune response. “But we don’t know if a particular drug, for example, intended to regulate the immune system will also activate the TB bacteria, so we’re looking for biomarkers that will help us make these predictions.”

The Emory TBRU is supported by clinical, administrative, and immunological cores that provide critical technical and logistical infrastructure, as well as data management and analysis.

Emory researchers also have identified blood-based biomarkers in patients with active TB that could lead to new blood-based diagnostics and tools for monitoring treatment response and cure. Published online in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, the study was led by TB immunologist Jyothi Rengarajan, assistant professor of medicine and Yerkes researcher, and Susan Ray, professor of medicine and epidemiologist at Grady Memorial Hospital.

“In order to reduce the burden of TB globally, identifying all TB cases is a critical priority,” Rengarajan says. “However, accurate diagnosis of active TB disease remains challenging, and methods for monitoring how well a patient responds to the six-to nine-month long, four-drug regimen of anti-TB treatment are highly inadequate.” —Gary Goettling