From the President

History and Wholeness

What is the consequence of deliberately or unconsciously forgetting the past? For George Santayana, famously, the consequence was being “condemned to repeat it.” But for many others, such forgetting may lead to illness, brokenness, and barriers that prevent them from moving forward in life with integrity. Consider the affliction of “conversion disorder.”

Occasionally persons develop physical symptoms—say, inexplicable blindness, paralysis, or sudden inability to speak—that have no apparent physical cause. Neurological tests and other diagnoses turn up no anatomical reasons for the problem. Often, however, such afflictions are preceded by emotionally or psychologically stressful events, some trauma, whose unpleasantness seems to be channeled into an actual physical disorder. Witnessing a horrific experience may lead to blindness—not because the eyes have been injured, but because the mind does not want to risk seeing more horror. Or getting angry enough to want to punch someone’s lights out may feel so frightening that the mind paralyzes the arms to prevent unwanted violence. It may sound like a movie plot, but, sadly, such disorders are real.

It is not too much of a stretch to suggest that something like this can happen in institutions, even in nations, as well as in individuals: collective blindness, collective paralysis, collective inability to hear with any acuity.

Emory University, like the US, has been on a long road to recovery from a kind of “conversion disorder,” a kind of elective amnesia, suffered for many years by our nation as well as by Emory. The trauma to be forgotten was the inhumanity of slavery, and the resulting affliction—the disordering of healthy communal life—was decades of Jim Crow laws, racism, and social discord.

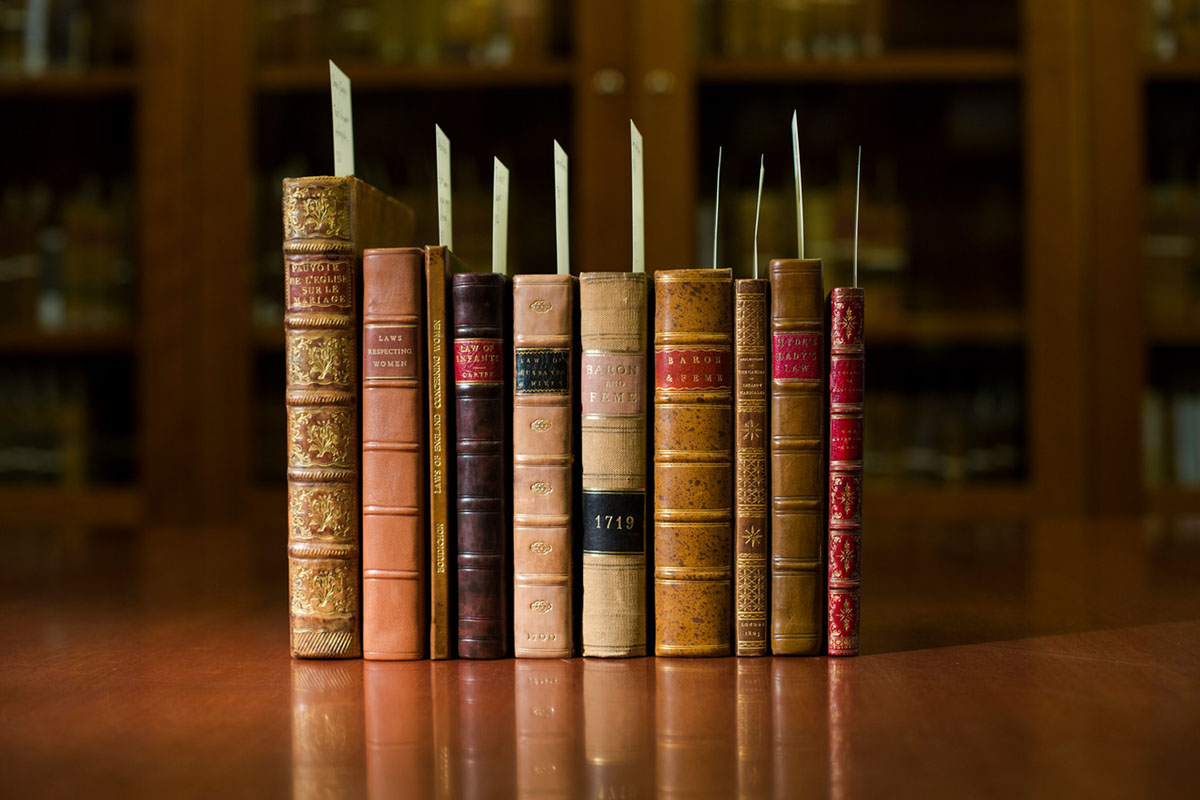

Earlier this year the Executive Committee of the Emory Board of Trustees issued a statement of regret for Emory’s “entwinement” with the institution of slavery during the early years of the College’s life and for the harmful legacy of slavery. While the statement grew out of a campuswide conversation prompted by our extensive, five-year Transforming Community Project, in every respect the statement was neither a culminating end point nor exactly a beginning. It is, rather, the latest in a long series of chapters in Emory’s history, some courageous, others less so, dealing with the legacies of slavery and racism.

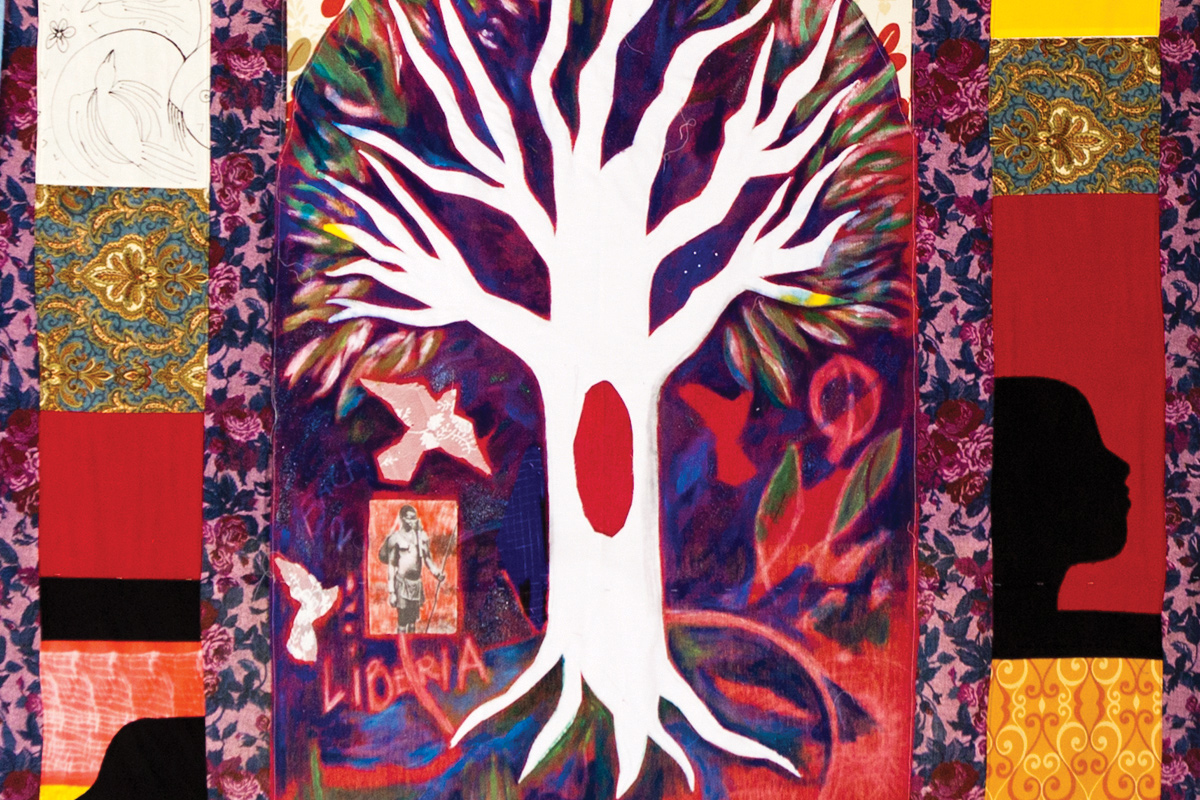

The roots of that statement, like the roots of our university, reach deeply into America’s past, and if we seek to trace out those roots we find a particular strand gripped by Georgia clay and flourishing as early as 1836—indeed, earlier. This root we know as slavery. But we could also call it by the name of inhumanity. For it was a way of life that prevented everyone involved in it from achieving the full potential of their humanity—whether it was the enslaved, whose humanity was degraded by bondage, or the enslaver, whose humanity was eroded by hubris and blindness.

The Emory University motto, drawing on the Book of Proverbs, is Cor prudentis possidebit scientiam, which we translate, “The wise heart seeks knowledge.” In this, the 175th year of Emory’s existence, we can be grateful that some wise hearts sought knowledge and aimed not to forget the trauma of that period, so that we could reclaim the wholeness, the integrity, of our university.

One of those wise hearts was a president who, in the 1880s, incurred the opprobrium of many fellow Georgians by creating opportunities for higher education for freed slaves. Another wise heart was an Emory professor who in 1902 risked his career in speaking out against lynching and calling his fellow Southerners to the rule of law. Other wise hearts included faculty members who in the 1950s acted in behalf of desegregated public schools in Atlanta and Georgia. Still others included trustees who in 1962 took the step of suing the state for the right to integrate Emory’s student body. And today those wise hearts include men and women of all races and colors who refuse to let Emory or America forget either the trauma of the past or the long way we have come toward the full restoration of our humanity.

Our community is now recovering from its elective amnesia. As the University observes its 175th year, it is important to the integrity and health of Emory for us to remember who we were and who we have become—to recall our history in order to claim our wholeness. Only thus can we move to a brighter future. The way the trustees put it in January was this: “As Emory University looks forward, it seeks the wisdom always to discern what is right and the courage to abide by its mission of using knowledge to serve humanity.”

May it be so.